Why is London's phone signal so bad?

Plus: Will the tube strikes actually go ahead; the capital rises up in support of a cat.

Welcome to London Centric, where we’ve been putting the winter jacket back in the cupboard after someone set the dial on the capital’s weather to “strangely warm and spring-like”.

Sometimes this outlet will ask big questions, such as who is going to replace Sadiq Khan as Labour’s mayoral candidate, investigate strange goings-on in one of our cultural spaces, or look at the behaviour of our elected officials. (Thanks to the Times for following-up London Centric’s latest investigation in this morning’s paper.)

But sometimes it will look at those annoying everyday issues that impact life as a Londoner. For today’s edition I went deep down a rabbit hole, asking: Why exactly is London’s mobile phone signal so bad?

I’ve been running around the capital with my phone, speaking to experts about how it’s possible to have the 5G logo showing, with full bars for signal, yet still be unable even to send a WhatsApp message. In the process, I discovered an unexpected London hotspot where you’re guaranteed super-fast data speeds.

Scroll to the end to find out why the capital’s phone signal is so bad — and how our politicians could fix it. And if you’ve got another everyday issue you want investigating, do get in touch.

London Centric’s 25% off launch offer will have to come to an end soon. If you’re one of the thousands of people reading the free version of this email, enjoy what you’re reading, and believe in supporting a new form of local journalism for London, then please do consider upgrading now. You’ll lock in the discount for the next twelve months.

There are no oligarchs involved in funding London Centric. Just readers like you who are willing to support independent journalism.

Will there really be a tube strike next month?

Sometimes how a news story emerges says as much about the underlying reality as the story itself. Just six people (including London Centric) were watching the livestream of Wednesday’s Transport for London board meeting when TfL boss Andy Lord let slip that rail workers’ unions ASLEF and RMT had voted to go on strike next month over pay.

Usually, when a union calls a strike it loudly announces the decision itself.

Instead, it took calls to the ASLEF press office to elicit a press statement confirming that tube drivers had voted overwhelmingly for two days of all-out strikes on Thursday 7 November and Tuesday 12 November, effectively shutting the network down on those days. The RMT union, whose members include staff working in stations, control centres, and engineering divisions, also later confirmed plans for a rolling series of walkouts from Friday 1 November to Friday 8 November.

So what’s it all about? Andy Lord told the TfL board meeting it was “extremely disappointing” that ASLEF had rejected a proposed pay deal worth 4.5% to tube drivers, which he said was in line with the deal accepted by train drivers on the national network. ASLEF described the same pay offer as “3.8% plus a variable lump sum”, and said it would mean tube drivers “stay on a lower salary than drivers on other TfL services while working longer hours”. A key sticking point is the claim that drivers on the TfL-operated Elizabeth Line and London Overground have better conditions that tube drivers, including pay for meal breaks. The RMT is particular upset by an issue around collective bargaining.

Both unions offered wriggle-room to walk away from strikes (which would ensure their members don’t have their pay docked for the hours they aren’t working) if TfL ups its offer.

Another round of talks is imminent. Don’t cancel your plans for those strike dates just yet.

Preposterous London property of the week

£20,000-a-month for a two bed house on Portobello Road in Notting Hill with a slide taking up much of the living room.

London Centric is currently investigating the ongoing cyber attack at Transport for London. If you want to talk, in confidence, about the reality of what’s going on behind-the-scenes at TfL, then please get in touch. And if the cyber attack has impacted you, your friends, or your family I’d love to hear from you.

Email hello@londoncentric.media or click here to send a WhatsApp.

Emergency overdose of meow meow

Among the many issues on health secretary Wes Streeting’s plate (like trying to make the NHS function as cohesive whole, digitising health records, or dealing with hospitals charging £2/hour for wheelchairs) there has been another crisis this week: the fate of an elderly moggy in Walthamstow.

Defib the cat has lived in the local ambulance station for the last sixteen years, having been rescued as a kitten and looked after by staff ever since. But this week an anonymous petition revealed that the ageing feline was set to be evicted following a change in management. Tens of thousands of people rushed to object. Paramedics tweeted about their heartbreak. The ambulance service defended the eviction on the basis that some staff were allergic to cats and Defib was increasingly at risk of being run over by vehicles.

Amid a growing outcry the boss of the capital’s over-stretched ambulance service has backed down. Daniel Elkeles announced a policy reversal on Thursday: "I have heard all the feedback about Defib the cat. I do believe that my team were trying to make the best decision for both Defib and all our staff. I have listened to the views of the public and many of our staff and we have now agreed that Defib can remain at Walthamstow Ambulance Station. Defib is much-loved by staff at Walthamstow Ambulance Station and evidently, he has won the hearts of the public too.”

Why is the phone signal so bad in London?

I was trying to interview telecoms analyst Matthew Howett about the problems with London’s phone coverage but there was a problem: The call kept failing due to poor signal.

Howett runs his business from an office close to Liverpool Street station, while I was speaking from my desk in south London, directly opposite a phone mast on top of the building across the street. But maintaining a stable connection between the two of us in a supposedly global city was impossible.

“The networks want to fix it,” said Howett. “Because you’re not going to give them money for something that doesn’t work. But they are not being helped to get the stuff done that they need to do. It’s become a government problem.”

The main issue, he said, are the challenges that networks face when it comes installing the telephone masts that enable you to send a WhatsApp, check your email, and refresh TikTok while on the go. It’s a combination of planning policy failure, opposition from local residents, and lack of backing from central government. And it’s going to take years to put right.

Ask Londoners where in the capital the phone signal is particularly bad and you’ll get a wide spread of answers: Covent Garden. Hampstead. Stratford. In the modernist concrete bunkers that make up the arts venues on the South Bank, and in the Barbican, people have been unable to download the e-tickets they need to access events. Railway lines out of Waterloo through south west London seem to come with extended periods of data blackouts. And you may find yourself hovering in the far corner of your local shop trying to download a QR code to collect a parcel, while the queue grows behind you.

To understand what’s going on, you first have to understand how a mobile phone network operates. In its simplest form it is like a super-powerful outdoor wi-fi network: your phone connects to a mast, which might be a modest lamppost-style pole on a street corner, or a big chunky metal lattice structure standing some distance away on top of a hill or a block of flats. Your phone then sends and requests data from the mast, which in turn deals with the request by communicating with a central network, usually using an underground fibre optic cable similar to your home broadband connection.

In common with all major cities, London is already at a disadvantage because it is full of tightly-packed streets with tall concrete and plate glass buildings, which block signals. According to Howett, a drive to fight climate change and increase energy efficiency means new windows often contain a lot of metallic products, creating a Faraday cage which block electromagnetic signals. Unless a developer chooses to spend extra money voluntarily putting a mobile phone signal repeater inside the building then people will find their signal is impacted.

One of the biggest areas of confusion for Londoners, according to Howett, is the difference between your phone being able to connect to a mast and it having the ability to actually download data at a reasonable speed. This might mean that your phone is showing a strong signal but you have absolutely no ability to use data services to receive WhatsApps or reply to that Instagram DM.

“The bars are just referencing the strength of the signal that you’ve got to the site,” he said. “But the site and its connection to the internet are reliant on how many people are connected to that site. It’s like a cake: You’ve got to split it a lot of ways. You might have five bars because you’re connected to the site but if there’s no capacity then you’re not going to have a good experience.”

When 4G was first switched on very few phones had the ability to access it, so there was lots of cake to go around. As a result the data download speed for many Londoners really was higher a decade ago compared to what they might experience today. Now, with the installation of 5G networks and proliferation of phones using it, more and more devices are trying to latch on to a small number of masts – meaning the cake is divided so much that it becomes a useless pile of crumbs.

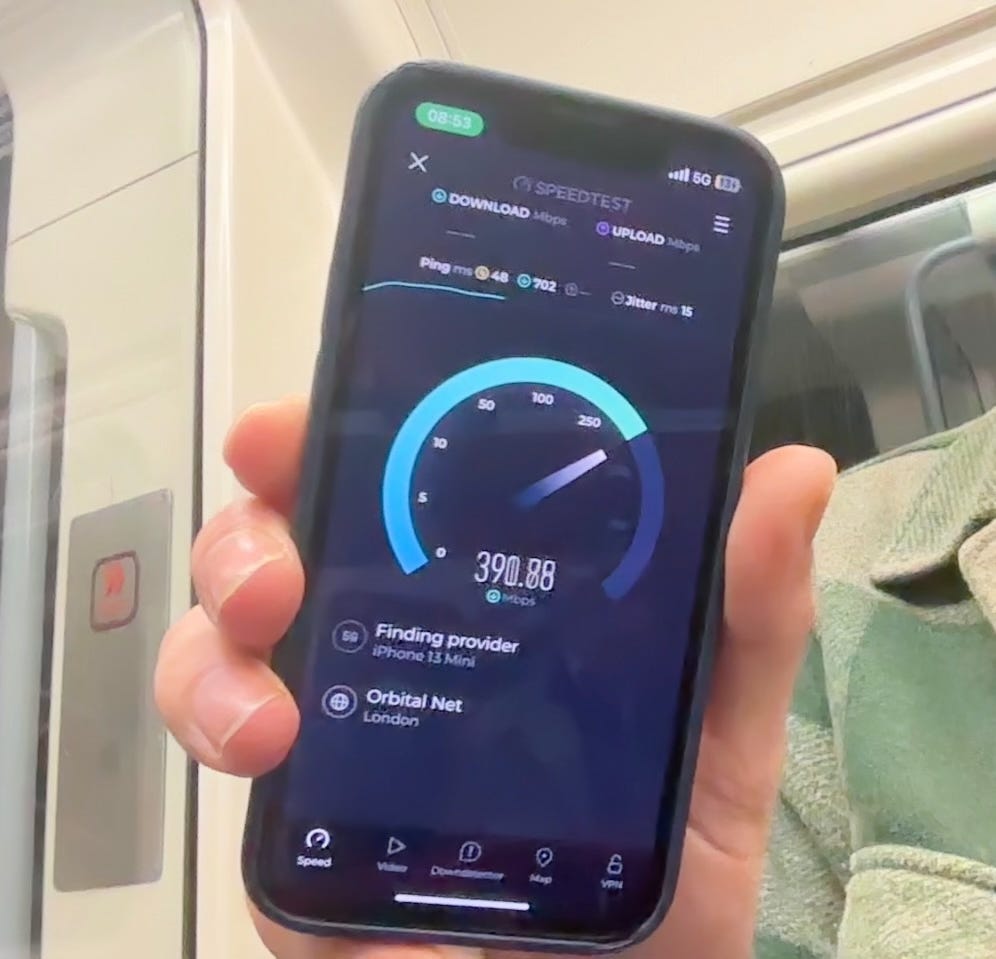

Astonishingly, tests carried out by London Centric found that in several high-profile areas of the capital the best place to find a fast 5G mobile data connection is now hundreds of feet under the capital in deep tube tunnels. This is thanks to new equipment – known as “leaky feeders” – installed in recent years under a contract with Transport for London.

In a damning indictment of the capital’s outdoor mobile infrastructure, if you want to tether your laptop to your phone and work remotely you might be better off tapping into the tube network and doing your work while riding around at 40km/hr underneath London. (Much of this article was written on the tube in this manner.)

On a packed rush hour Jubilee line train to Canary Wharf on Thursday morning it was possible to download data over EE’s network at 217mbps (megabits per second), as fast as many home broadband connections. But the moment you go above ground and are surrounded by the financial district’s skyscrapers the data download speed falls by more than three quarters to 49mbps.

Get back on the Jubilee line heading east from Canary Wharf and, thanks to the train emptying out, it was possible to hit a super-fast 371mbps on 5G in a tunnel deep under the Thames, enough to download an entire film in little over a minute. But on arrival at Stratford station there was no data connection on many platforms.

Jump on the Elizabeth Line to central London and the in-tunnel data speed returns to 203mbps – but outside Tottenham Court Road station, where you might be trying to meet a friend, it immediately falls to a barely-usable 2mbps. Even wandering around the corner to the middle of an empty Soho Square, free from obstructions, did little to improve download speeds.

The solution to all of this is to install more masts with greater capacity. Gareth Elliott works for lobby group Mobile UK, which represents the interests of mobile phone network providers. He said the biggest issue the operators face in London is the planning system, with local councillors across the capital politically incentivised to object to new masts at all costs – either on aesthetic grounds, or over dubiously-sourced fears about the supposed health impacts.

He said an ongoing issue is that councillors and local residents check coverage maps, see the capital is effectively 100% covered for signal, and conclude there is no need for more masts: “While the general perception is that a dropped call or slow connection is a coverage issue, it is more likely to be a capacity one.”

At the same time, Elliott said the networks he represents also receive complaints from the same local politicians about the lack of data capacity in their area, without making the connection between the two issues. In some areas council leaders delight in boasting about how many masts they have blocked on behalf of local residents.

You don’t have to go far to find recent examples of London’s opposition to masts. In Haringey the council apologised after allowing a mast to be built near a cricket club, saying it was a “regrettable error”. In Mitcham local residents have been fighting a mast that will “cast a shadow” over a village green. In Romford residents called the installation of a mast on their block of flats a “public health failure”.

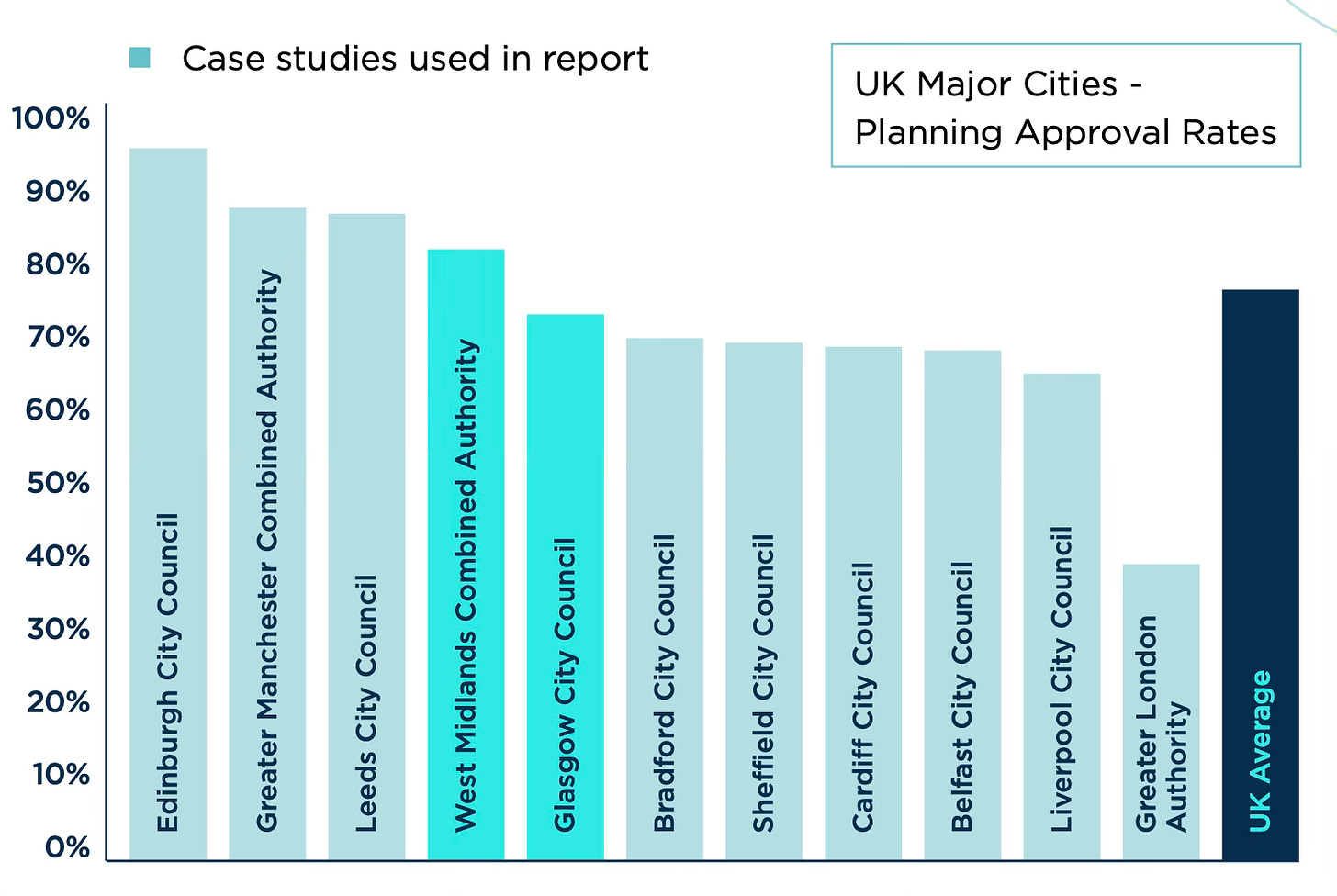

The end result is that in London it is uniquely hard to get permission for new equipment. According to Mobile UK’s internal data in Greater Manchester, Leeds, and Edinburgh more than 80% of requests for new masts are approved at the planning stage. In Greater London this approval rate plummets to less than 40%, one of the worst in the country.

The places most in need of extra capacity, such as Soho or the West End, are also among the areas with the highest levels of architectural protection for their old buildings. Large swathes of the capital are conservation areas that have much stricter planning rules on how equipment must look. Although a modern 5G mast might be relatively slim, it still requires a series of chunky power supplies and networking equipment to be located in cabinets at street level. In some local authorities wealthy residents running letter-writing campaigns will do everything they can to block new masts.

Howett said some London councils are notoriously difficult to deal with: “Kensington and Chelsea famously hate street cabinets which you need to go with the mast.”

Ultimately, Elliott said, there has to be an acceptance among the public that bringing a reliable 5G signal to people means placing masts in locations “dependent on radio physics”, rather than somewhere considered more aesthetically pleasing by councillors.

The rapid redevelopment of London also means many older buildings with functioning masts are being ripped down – leaving the mobile networks scrabbling to find suitable nearby sites for replacements. Equally, a new tower block might be erected which blocks a signal relied on by local residents.

And as anyone who has attended an event at EE-sponsored Wembley Stadium or the O2 Arena knows, these venues can quickly become overwhelmed by too many people trying to connect at the same time. This could be easily solved by the installation of “neutral hosts” providing signal to all networks – but that’s not in the interests of mobile phone network sponsors. They want people to know that you have to switch contracts if you want a reliable signal at those venues.

There is one other uniquely British issue that has impacted the mobile network in London: Huawei. The Chinese tech company was a relative minnow in the global technology world until BT made it a supplier of choice in the 2000s. This support from British customers built it into a global giant but was also its undoing, amid concerns from US President Donald Trump and Boris Johnson’s former chief of staff Dom Cummings that its role in the UK’s 5G network could provide a backdoor for Chinese spies.

In 2020 the order went out from central government that all Huawei kit had to be removed. Billions of pounds had to be spent by the networks ripping out functioning 5G equipment, sourcing replacement kit from other suppliers such as Nokia and Ericsson, and installing it. The process set back the rollout of 5G capacity by years, according to Howett, who retains doubts about the decision: “There’s never been evidence of espionage by China in the network. The national cyber security centre took apart every piece of equipment deployed in the UK and British engineers never found a problem. The only problem they found was some sloppy code from Chinese developers.”

He said London has to decide between having a city where people can get data on the move, or one which is aesthetically clean and free of masts: “You walk down the streets in Asia and there are wires hanging from building to building, because people expect connectivity. Within 10 minutes of moving house you expect new full-fibre broadband and there’s shame on the operator if they haven’t installed it by then. People move in, they want the internet, and they don’t care if there is a cable dangling. We care a little bit more about what people see at street level.”

But the ultimate question remains: Which mobile service provider should Londoners choose for the best signal? Howett has an extreme solution that means he’s almost always connected: “I’ve got a SIM card from every network.”

Enjoy what you’ve read? Want to read more? All feedback is appreciated – email hello@londoncentric.media or send a WhatsApp.

And if you’ve been forwarded this by a friend, please do click below to subscribe.

An obvious shortage of (ornate Baroque) water fountains in London, a need to hide aerial tower masts. The solution is staring us in the face (and Sir Richard Wallace already did this for Paris! except the 5G bit). Some may quibble around mixing water and electricity but I'm sure those are just minor details.

I'd love to know why Stratford station is such a barren wasteland for mobile data - it's surrounded by new builds with plenty of masts on the roofs. I now get a great signal in the tunnels, but it dies completely once I get above ground, and I have to wait until several stations further east.