River swimming and dead dogs: Who actually owns the Thames?

Plus: Book libraries banned from London Underground stations and are the capital's rats multiplying?

In the six months since London Centric launched we have often investigated the businesses and individuals who own the capital’s public spaces. From parks to shops and cinemas, the places in which Londoners live their lives are controlled by people and companies who aren’t household names, and who often engage in complex ownership structures and business practices.

Today we have a story about one of London’s most iconic public spaces: the River Thames. It’s the city’s greatest artery, the central point around which it grew, a centre of commerce and activity for thousands of years. The Thames has been reinvented for every generation that has lived or worked around its banks or crossed its bridges.

Yet London’s river is not owned and governed by the general public but by a private trust. And right now now the future of the river and its owner is being decided in a nondescript meeting room near Liverpool Street station.

Scroll down to find out who really owns the Thames.

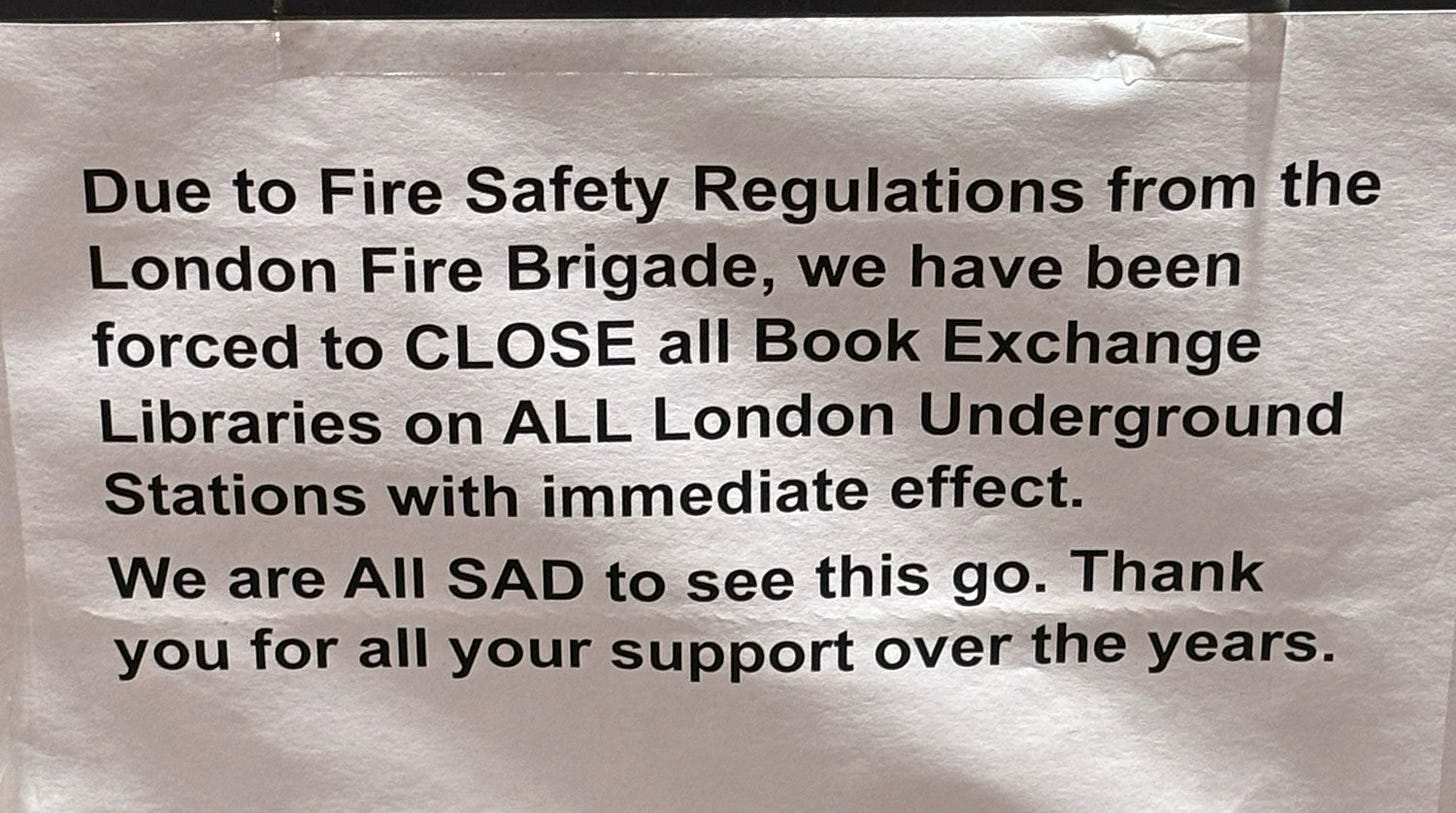

Book exchanges removed from London Underground on safety grounds.

For decades some of London’s tube and railway stations have featured book exchanges, where passengers have been able to drop off their favourite book and swap it for a well-thumbed copy of an Andy McNab novel. Now, the book exchanges appear to be vanishing from Transport for London properties on safety grounds.

London Centric reader Paul Lang sent in a printed noted attached to the book exchange at his tube stop on Tuesday. “This sign was on the book exchange at Oval,” he said. “The shelves were turned round to face the wall.”

London Centric’s initial inquiries suggest this policy is being applied unevenly, with a book exchange still in place at Stockwell station on Tuesday night. However, a similar library at Lewisham station run by local man Michael Peacock, a book enthusiast who in a past life played a key role in rolling back the UK’s obscenity laws, is also at risk under regulations which require flammable material to be held securely in sub-surface stations.

Transport for London did not immediately respond to a request for comment on whether a blanket ban is being enforced and what prompted the change.

London Centric is funded by its readers. If you want to take a stand against clickbait journalism, fund original reporting about the capital, and read today’s members-only investigation then please consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

Ask a London expert: Is the capital’s rat population exploding?

“I’ve lived in West Hampstead for more than 30 years and might see one rat in five years. Now, I see this kind of thing most days. I understand that many major cities around the world have seen exponential increases in rat populations. But it wouldn’t surprise me if London were outpacing the others.” - London Centric reader Martin Vogel.

Headlines seem to suggest never-ending growth among London’s rat population, with one recent ranking describing London as the second rattiest city in the world. But, with the not-entirely-impartial pest control industry acting as the main source of rat data, how factual are such reports?

Since there is no proper research on the subject, experts have “no idea” whether rat numbers are really increasing, said Professor Steven Belmain, a rodent and pest scientist at the University of Greenwich. Observational bias and people spending more time outdoors since the pandemic mean rat sightings might increase but this doesn’t necessarily mean more rats. And while rat numbers press released by the pest control industry seems to go “up and up”, he says this says as much about declining human tolerance for pests as the pests themselves.

Nonetheless, issues like litter and striking refuse collectors “exacerbate rodent problems”, while construction sites can drive rats into more urban habitats. Rodent resistance to poison is “certainly a phenomenon in some parts of London,” he added, with data collected by the Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee suggesting the capital’s rats may be adapting and surviving attempts to kill them.

Belmain said there’s little risk of giant rats bounding down London’s streets any time soon – most British rats that live above ground (unlike their sewer-dwelling counterparts) have a maximum size of around 600 grams.

Do you have a question you’d like putting to a London expert? Send a WhatsApp or email.

London Centric Investigates: Who actually owns the River Thames?

By Rachel Rees and Jim Waterson

In a basement meeting room in the City of London, a month-long battle over who owns the River Thames is currently underway. Every morning a group of lawyers, activists and environmentalists traipse in and give evidence to the inquiry over arcane points of law.

The Thames feels like something that belongs to all Londoners: It is the city’s iconic waterway, the reason London was founded by the Romans at this location, and the home to some of the capital’s most recognisable sights. Sadiq Khan won re-election last year on a pledge to make London’s rivers available for swimming by 2034, inspired by other European cities such as Zurich and Paris.

Yet the Thames is not controlled by the elected mayor, the local borough councils, or the residents of the capital. Instead, London’s river is run by a private business: The Port of London Authority (PLA), a largely self-governing trust.

Paul Powlesland, a barrister who is taking part in the hearings, described the PLA as “effectively unaccountable”.

“If Londoners don’t like the way that the planning of London in general is done, they can vote their mayor out. But if Londoners don’t like what is happening with the Thames, there is absolutely nothing they can do about it”, he said.

The PLA, the “owner of the bed of the tidal Thames”, manages 95 miles of the river. A few years ago the organisation announced it wanted to “modernise” the rules under which it operates with a series of tweaks, such as changing the requirements around autonomous vehicles on the river and enabling the wider use of email.

Usually, such changes — known as a Harbour Revision Order — would go through with few objections. But unhappy Thames residents, river users and environmentalists have accused the authority of a “power grab” and forced a series of public hearings which raise far broader concerns about the role of the PLA. Issues range from whether the river will ever be made clean enough to swim in, whether homeowners can be charged thousands of pounds for having a balcony that overhangs the river, and who is responsible for retrieving dead dogs from the water.`

At the heart of the hearings sits a bigger debate: What is London’s river really for? And who should be in charge of the Thames?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to London Centric to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.