Ageing, static and skint: Nine charts that explain what's going on with London transport

How the ability to travel around the city shapes the capital, its residents, and the lives we lead.

Welcome to London Centric where we’ve been enjoying the longer evenings. Yes, it’s not even the winter solstice but sunset in the capital tonight will be a few seconds later than yesterday, signalling that summer is almost on its way.

There’s a festive selection box of exclusive stories coming up later this week for paid subscribers – but for now I want to talk transport.

Transport is what makes London tick, drives its economy, and makes it possible for this chaotic mess of nine million people to function as a city. If you can’t get around London in a fast and affordable way then you’ll have to turn down jobs, meet fewer friends, and reduce your mental horizon. Investment in transport can make a real difference to the lives and health of the city’s residents. And if you stare long enough at the tea leaves of London’s transport data you can see the signs of the city that the capital has become: Ageing, more static and increasingly skint.

Every year Transport for London releases a massive data dump that sums up the state of the capital’s transport system. You might have seen some cherry-picked press released lines in other outlets but at London Centric we savour such documents and have taken some time to mull them over. What follows are the most intriguing and unusual details digested from hundreds of pages of data.

Looking for a last-minute Christmas present?

Why not support a new approach to local journalism by buying a gift subscription to London Centric. You can schedule the subscription to start whenever you want and if you buy it this week then drop an email to hello@londoncentric.media and I’ll post you a specially-commissioned physical gift card to hand over on the day.

1. London is becoming an older (and more female) city.

There are fewer young adults living in London than there were a decade ago. This is largely driven by a stark 7% fall in the number of men aged 25 to 34 making the city their home. This is compared to a slight increase in the number of young women of the same age. This gender split has interesting implications for transport usage: Men are more likely to drive cars and take trains, women are more likely to walk and take buses.

One of the many factors crowding out young adults is the fact that boomers, Gen Xers, and older millennials are hanging around the capital in greater numbers and not fulfilling their traditional duty of selling up their roomy family homes and moving to Surrey or Essex.

The problem for TfL is that younger Londoners were traditionally the people who travelled around the city a lot as they tend to be more physically active, have more hobbies, and go out for fun. But in 2024 these young people are too busy dealing with the cost of living crisis and paying their salaries to private landlords and struggling to afford the cost of travel, one of many issues contributing to TfL’s shaky finances. There are major societal implications here. If you stay at home in your overpriced flat then it’s harder to form relationships with other young Londoners, which in turn hits the capital’s birth rate, and ultimately — in a decade’s time — the number of children taking the bus to school.

When Ken Livingstone became London’s first directly-elected mayor in 2000, he presided over a city containing just over seven million people. The capital’s population subsequently soared to almost nine million but this population growth has slowed in recent years. London is one of the few places in the UK where there are still more births than deaths. But the city is reliant on maintaining high levels of immigration from overseas to ensure its population doesn’t decline, with 41% of payrolled jobs in the capital held by foreign workers — double the national average.

As Transport for London put it starkly when looking at the outlook for its network: “There is little suggestion of strong population growth in London in the short to medium term.”

2. Londoners are moving around the city a lot less than they used to.

The number of ‘trips per day’ taken by the average Londoner using any mode of transport (whether driving, taking public transport, or walking) has fallen by a quarter since 2007, on the eve of the financial crisis.

A trip is exactly what it sounds like, with TfL’s official definition being a “one-way movement from one place to another in order to accomplish a defined purpose”. A circular journey, such as a morning commute to work and then back in the evening, would count as two trips. Each trip might involve multiple forms of transport, such as walking to the end of a road to catch a bus before getting on the tube to the office.

This year, for the first time, the average Londoner took fewer than two trips per day. And when people do travel, they don’t go as far. The average distance travelled in London is now just 11.3km per person per day, down 14% on pre-pandemic levels. The length of time that Londoners spend travelling each day also decreased from 72 minutes in 2006 to 54 minutes in 2024. It’s a more static city.

3. Some people really are getting rid of their cars — and it’s creating two Londons.

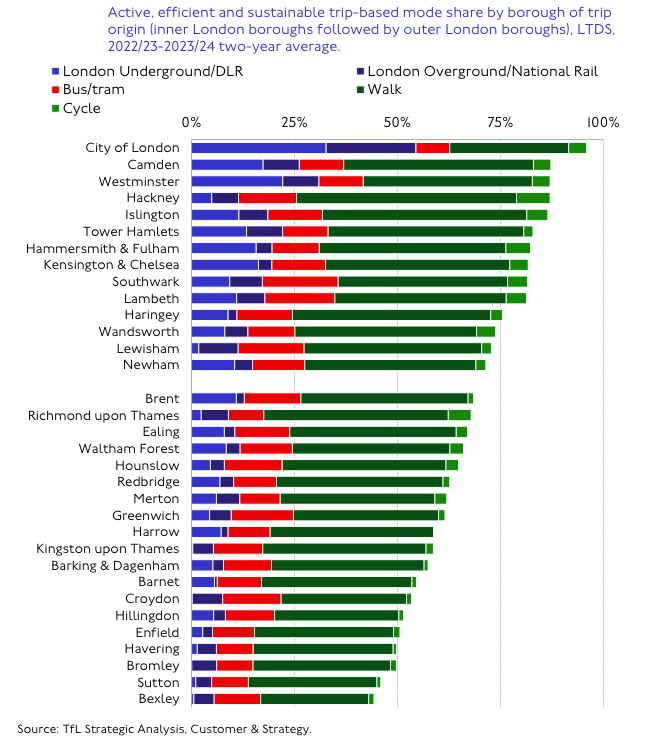

The London boroughs on this map in green are the areas where people are increasingly living without cars altogether. The boroughs in red and orange are where people are becoming more likely to have access to a car.

This is creating a growing schism between the capital’s centre and its suburbs in terms of how people get around. In Inner London 62% of households now live without access to a car, compared to just 33% of households in Outer London. If you’re a resident of Camden or Westminster or Hackney you’re deeply unusual if you drive around the local streets. If you live in Bexley, or Sutton, or Bromley then you’re the weird one if you don’t pop in the car to go to the shops or get to work.

Part of this split is due to the physical make-up of the outer boroughs, where lots of big suburban streets mean traffic can flow faster and you’re often further away from a reliable, regular public transport route or a safe cycling route.

This divergence has major political implications ahead of the next mayoral election, especially when talking about concepts such as the “war on the motorist”, a phrase much loved by the recent Conservative government. (Although as London Centric revealed last month, one particularly radical plan to reduce car usage was dropped by Labour’s Sadiq Khan last summer amid political pressure.)

The inner boroughs with higher public transport usage tend to vote Labour. The suburban boroughs towards the bottom of this chart, where the car is king, tend to vote Liberal Democrat or Conservative.

Car drivers also tend to be wealthier. According to TfL, the typical car driver in London is a high-earner aged between 45 and 64 who is either in full-time employment or retired.

In the past, car ownership in the capital tracked London’s population: As more people lived in the capital, the number of cars on the streets also went up. This link has now been broken and overall London car ownership is in decline, contrary to the trend in other parts of the UK.

There has also been a substantial drop in the number of young people learning to drive, with only 46% of Londoners in their 20s holding a full driving licence. Many of them said that the cost of buying and insuring a car is the main issue stopping them from passing their test. At the same time, a quarter said they relied on family members to give them lifts — possibly because those young people are stuck living at home because they can’t afford their own place.

4. Flexible working patterns and the Elizabeth line have largely ended rush hour overcrowding on trains.

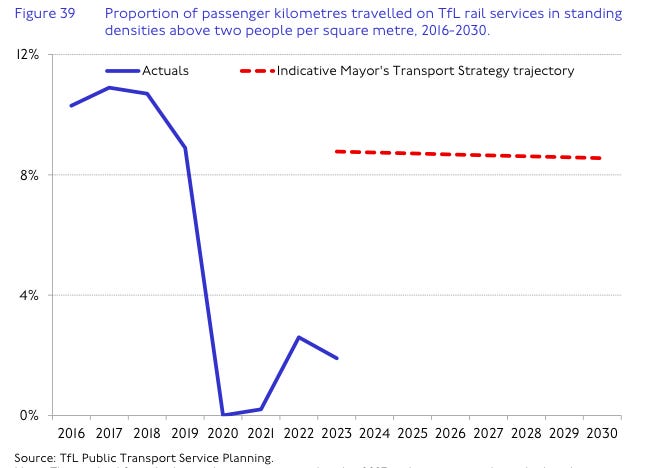

Prior to the pandemic, around a tenth of rail travel on TfL services (such as the London Underground and Overground) involved having your face uncomfortably crammed into the armpit of your fellow passenger.

Now, with the Elizabeth line adding capacity — and with many people doing the first meeting of the day at home on Teams before heading in after the school run — the stereotypical London rush hour crush has largely been eliminated. But don’t get used to it. Even with fewer journeys being taken per Londoner, TfL warns that “without further investment in capacity on our network it is expected that crowding will increase”.

5. Travel in London still hasn’t recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

Overall demand for travel in London is slowly approaching its pre-pandemic levels but this recovery is not as rapid as TfL expected, whether due to permanent social change or the sluggish economy.

Lower passenger numbers on public transport means less revenue for TfL. It also makes it harder to justify significant investments in new railway lines such as Crossrail 2 between Wimbledon and Tottenham or the Bakerloo line extension from Elephant and Castle to Lewisham.

The demographic breakdown is also notable, with white Londoners making the highest number of trips per day around the capital and black Londoners making the fewest.

6. Working from home has had a permanent impact and Wednesday is the new Big Night Out.

The number of Londoners who are actively encouraged to do their jobs from home has doubled to 1.6 million since the start of the pandemic, equivalent to around a third of workers in the capital.

The tube is one of the best proxies for office workers, as it’s more expensive than the bus and is heavily reliant on commuter traffic. This graph compares usage of the London Underground in mid-June 2024 to the equivalent period before the pandemic.

While the number of London Underground journeys on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays is pushing towards 90% of pre-pandemic levels, on Monday it’s stuck at just 79% of the pre-pandemic level — suggesting a fifth of London’s commuters have simply stopped coming in for the start of the week.

The table below also shows how London’s buses have seen similar but subtly different changes since the pandemic. Any number below 100% means people are taking fewer journeys in that time slot, while any number above 100% means people are taking more journeys in that time slot.

The data shows the morning rush hour between 7am and 10am is now substantially quieter, which might explain why you’re now less likely to be turned away by a full bus. Yet there has been a boom in bus travel after 10pm on Wednesdays and Thursdays — possibly as people travel home late from mid-week post-work drinks.

7. The streets of central London really are emptier.

Walking rates across the whole city are up slightly on pre-pandemic levels. But there has been a particularly bad hit to central London foot traffic, amid the general decline in office-based work and shopping trips.

According to TfL, during the first half of 2024, the number of pedestrians walking around central London settled at around 90% pre-pandemic levels — which means central London’s shops, offices, and restaurants have fewer potential customers.

8. The tube has become much more accessible to wheelchair users but progress is slowing.

Anyone who uses a wheelchair (or has pushed a buggy) around London will know the difficulties of getting to-and-from some of the platforms, especially in central London. Although there has been a big investment by TfL in making stations accessible, meaning journey times are getting shorter for people who require step-free access, that progress is starting to slow down as many of the easier projects have already taken place.

There were no new step-free stations opened in 2024, with Knightsbridge tube station the next one to be converted. (Although one of TfL’s bigger issues is ensuring the lifts that are already in place are actually working.)

9. Cycling is more popular after the pandemic but is still a niche form of transport.

Cycling boomed in the pandemic, aided by the rush to invest in bike lanes and low-traffic neighbourhoods, which has pushed the number of bike journeys up by a quarter to 1.33 million journeys per day.

Yet the overall picture is more mixed. Cycling remains a fairly niche way of getting around the capital compared to buses and the tube, while previous TfL research has shown it’s a mode of transport largely used by teenagers (who are short on cash and can’t legally drive) or older, richer, white men. Shaking the perception that it’s for those two demographic groups — potentially by embracing the ability of rental e-bikes such as Lime and Forest to entice new demographics into cycling — will be key to moving the dial.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please forward it to a friend. London Centric has no corporate owners and relies on word-of-mouth for distribution.

Want to support local journalism?

Have something to share? Please get in touch over email or WhatsApp or leave a comment.

I'm surprised at the claim that overcrowding is a thing of the past. Try getting an overground on the windrush line and changing to the jubilee at Canada water! It's madness at rush hour

Please can you do a piece on potential damage to hearing from the noise of the tube. I know some remedial work is being done but it’s excruciatingly loud on several lines.