Last of the Christmas meat auctions

Plus: Ocado fails to deliver dinner to Londoners, an update on Drumsheds, and the spread of surge pricing across the capital's pubs.

Anyone sensible already knows what they’re eating for their Christmas dinner. Instead, I’ve decided for the second year running that my family are relying on Smithfield Market’s annual Christmas Eve meat auction. You turn up with a wallet of cash, see what’s available at rock bottom prices, and hope for the best.

Smithfield has, in various forms, hosted a meat market for the best part of a millennium but now has just five years left to operate after the City of London gave up on plans to relocate it to a new site in Barking.

This means you’ve only got a few years left to attend Greg Lawrence’s annual carnival of festive fleshy excess in its current setting under the Victorian arched roof, an extraordinary event that is still unspoiled (for now) by TikTok virality and, unless you’re vegetarian, is one of the most extraordinary things you can attend in the capital at Christmas.

Lawrence had a chat with London Centric ahead of this year’s event, explained why it was such a hit, and also gave us an exclusive about a top-secret plan among the existing butchers to build a New Smithfield meat market on an as-yet-unnamed secret site in London — albeit without the direct involvement of the City of London.

Scroll down to read the piece.

Buy a London Centric subscription as a present and I’ll hand deliver a gift card to your door on Christmas Eve.

After a last-minute gift idea that also supports a new sort of local journalism about the capital? Join the (actually suprisingly large) number of people who’ve already bought a gift subscription to London Centric for friends and family by clicking here. Last Friday’s edition contained exclusive stories that were followed-up in the Financial Times, the Guardian, and Mixmag — and there’s not many publications that can say that.

If you’re a Londoner who lives in zones 1-3 you can STILL receive a physical London Centric gift card to hand over on 25 December, as I’ll be doing a final round of in-person deliveries before dawn on Christmas Eve. Just buy the gift subscription, email your address to hello@londoncentric.media, and I’ll post a complimentary gift card through your door.

Exclusive: Ocado tech breakdown leaves capital residents without Christmas dinner.

Middle class Londoners relying on an upmarket supermarket delivery service might not attract a lot of sympathy. But over the weekend London Centric has learned that something went very wrong at one of Ocado’s high-tech warehouses, resulting in long-booked Christmas orders being delivered across the capital without any chilled or frozen food.

One London Centric reader said “literally the entire Christmas dinner bar the parsnips was missing” and shared a receipt showing how dozens of items — including chicken, potatoes, butter, carrots, milk, gravy, herbs, salmon, and even pigs in blankets — had been missed off. And they weren’t alone. Dozens of others customers who received deliveries on Saturday and Sunday also said all the fresh produce was missing. As one customer put it: “Christmas delivery has arrived but all chilled and frozen items are missing. Loads of crackers but no cheese to put on them!”

Unlike most other supermarket delivery services that use humans to pick good from local stores, Ocado relies on high-tech depots run by robots, including one building in Erith, south east London, that claims to be “the largest automated warehouse for online groceries in the world”. (Honestly, it’s astonishing to watch it in action, at least when it works.)

One shopper who talked to London Centric said their delivery driver blamed a “robot malfunction” for the lack of fresh food.

Ocado, a listed company that prides itself on its technology capability as well as its ability to deliver the sort of premium food offering that defines Christmas for wealthier Londoners, confirmed that a now-fixed problem at an unspecified distribution centre knocked out some of its ability to deliver fresh food in the capital over the weekend: “We are aware that a small proportion of orders were not delivered as expected. This does not meet our usual high standards and we understand the inconvenience this will have caused, especially at this time of year. We are proactively reaching out to apologise to those affected."

Drumsheds drugs deaths led to review.

Following last week’s London Centric report revealing that the 15,000-capacity Drumsheds venue in north London was facing a review of its licence on safety grounds, the Metropolitan police has confirmed to us the circumstances that led it to intervene.

A police spokesperson cited three major incidents at the venue in recent months: A 27-year-old man died in hospital after attending the venue when it hosted drum and bass act Hybrid Minds in October; a non-fatal stabbing took place at a night headlined by Jamie Jones in November; and a 29-year-old woman died in hospital after attending the venue when it hosted Bicep earlier this month. Both the deaths are believed to be drug-related. The club’s licence is expected to be reviewed again in the new year.

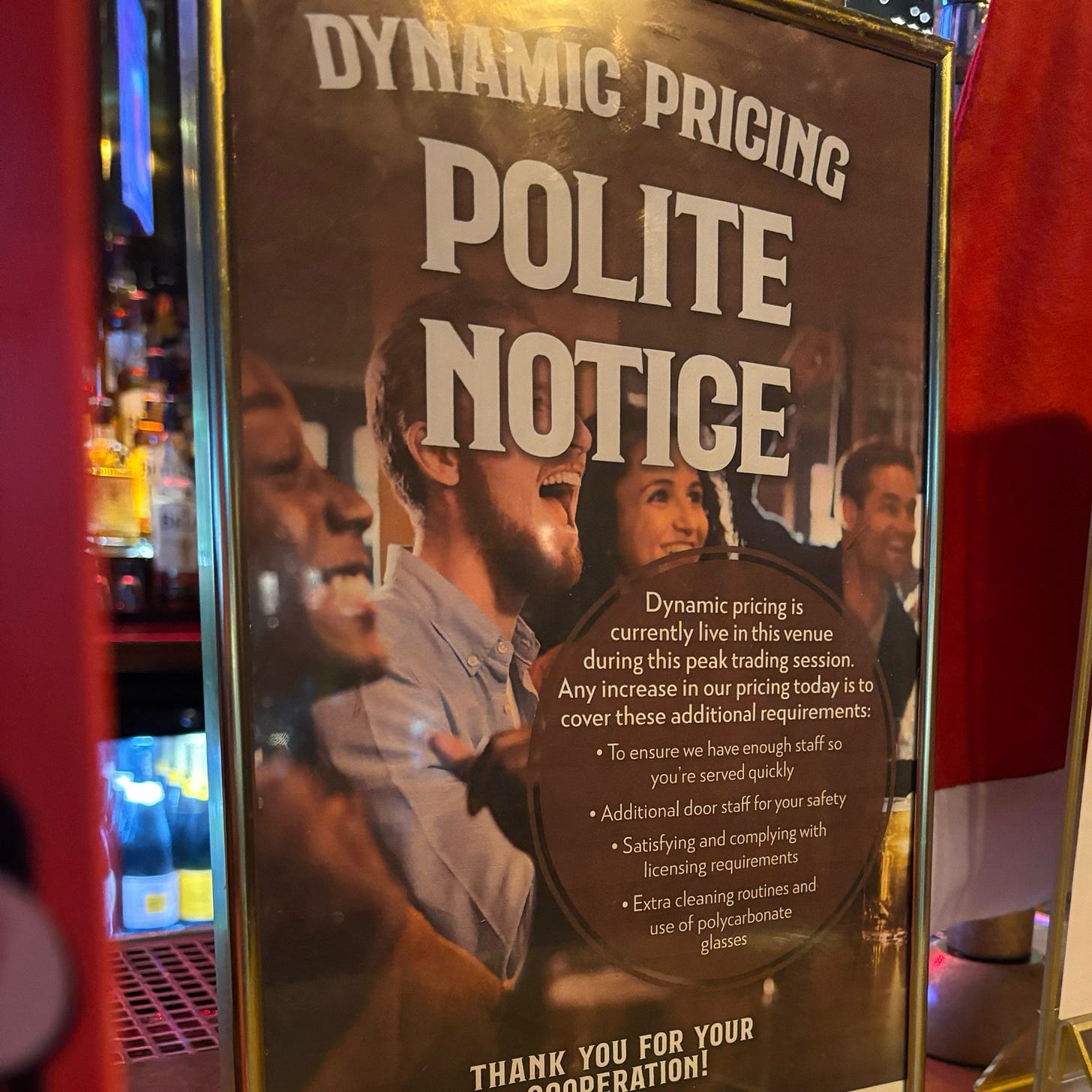

Surge pricing spreads across Soho’s pubs.

First it was Oasis tickets. Now it’s the price of a pint in central London pubs which is subject to Uber-style surge pricing. Earlier this year one O’Neills branch experimented with charging £2 extra per drink after 10pm and now the policy is spreading. London Centric reader Paul Lang sent this notice in from the Duke of Wellington, a gay bar in Soho, where drink prices were hiked to take advantage of the Christmas rush. A similar policy was in place at other nearby pubs also owned by the heavily-indebted off-shore pub company Stonegate. Bah humbug, as another famous London businessman might have said.

The last days of Smithfield Market’s Christmas Eve meat auction.

The last time I saw Greg Lawrence, the master of ceremonies at the annual Smithfield Market Christmas meat auction, he was reducing grown men to tears by throwing large lumps of meat through the air towards their grateful, grasping hands.

The patriarch of a long-established family butchers business, Lawrence has, for almost five decades, kept alive the long tradition of London’s meat wholesalers selling off their excess stock before they shut up shop for the festive period. What was, a few decades ago, a small gathering of Londoners looking for a cheap turkey has transformed into an annual media circus featuring surprise special cuts kept back for the occasion. Television crews from around the world attend to capture an event that purports to give a glimpse of an “authentic” London that doesn’t really exist, where locals fulfil trade animal flesh flanked by ornate Victorian ironwork and red telephone boxes.

Last Christmas, atop a specially-built catwalk stage in the middle of Smithfield meat market, the 75-year-old introduced each cut of meat in the same way a boxing announcer would introduce a fighter to the ring. Family members and staff in white aprons carried each new offering on their shoulders, while Lawrence used a wireless microphone to rhapsodise about the latest product: “This…. this is from Devon… It’s the best lamb you can possibly buy. This cut would cost you £100... well, supermarkets wouldn’t sell this cut, THIS only goes to the top restaurants in London.”

At this point the West Ham obsessive spotted a man in the crowd wearing a Leeds United hat and told him to take it off if he wanted any chance of being served, while making the crossed-arms hammers gesture.

Lawrence returned to toying with the crowd before finally delivering the punchline regarding the lumps of lamb being paraded around by his assistants: “It’s one price and one price only…. THIRTY POUND. English hind quarters of lamb! THIRTY POUND! UNBELIEVABLE!”

The crowd surged and hands full of cash were thrust upwards. Hats were waved on sticks in a bid to attract attention. Children were put on shoulders in the hope that would make a difference in what is less an auction and more a chaotic free-for-all. The only thing that matters is grabbing the eye of Greg, or his son (also called Greg), or one of his grandsons (one of whom is also called Greg). Get the nod of approval from a man in a white jacket and the strangers around you — even the ones who lost out on their own bids — will pass your cash to the front as a massive dirt-cheap slab of meat is crowdsurfed back towards you.

Some attendees spend their money too early and end buying something modest — a large piece of ham for £20, or a couple of geese for a tenner — only to miss the truly high-end show-off surprises that are kept back for the end. Others get carried away, buy too much and can then be found doing side-deals and swaps around the edge of the market. Butchers are on hand to cut up the bigger pieces of meat. Regulars who’ve been coming for decades turn up with suitcases to help drag their purchases home.

Yet this annual ritual, which is now held under the festive setting of the ornate ironwork Victorian market building at 10am every Christmas Eve, is due to end within a few years. After decades of speculation over Smithfield’s future, a plan to move the City of London-run market to a new site in Barking was formally abandoned last month. Instead, the existing wholesalers — including the Lawrence family business — are being paid to move out. Following centuries of trading, Smithfield’s time as a meat market is due to end in 2028.

When we spoke to Lawrence this week, he was excited for his annual moment in the spotlight and was planning a series of coin flip contests for particularly attractive pieces of meat. He talked with delight about the global news coverage it attracts: “One year we were sitting on Christmas Eve having a drink at home and my grandson’s phone rang. His Russian friend he’s at school with — we’ll call him Boris — is in Moscow and Boris says ‘Gregory, Gregory, I’ve just seen you on the news at Smithfield Market.’ They put it on the Russian news!”

But he’s also getting ready to say goodbye to the Smithfield building itself and its prominent central London location: “I’ll be emotional, because I’ve been down there since 1966. What I’ll miss will be the atmosphere and the characters on the market.”

“It really is a special place. But it’s the right move because of the road closures around Smithfield which make it hard for customers to get in and for suppliers to get in and out. The younger generations can’t expand their businesses because there’s no more space at Smithfield.”

What is now a modern market with spotless hygiene standards and refrigerated units began life as open land outside the historic city walls of London, which also doubled as a regular execution site (William Wallace of Braveheart fame died here in 1305) and the location of the decadent annual Bartholomew Fair.

Farmers would drive herds of cattle from outside the capital to Smithfield, where they would be sold and slaughtered to feed the city. As London expanded during the Victorian era it became too chaotic to have cattle wandering through the streets of the capital, so the live cattle market moved to a massive new site at Caledonian Market in Islington, where the clock tower still stands in a public park. Smithfield was reimagined as a hub for butchering with a purpose-built building, aided by the construction of the Metropolitan Railway which could rapidly carry animal carcasses from outside the capital into special sidings.

Smithfield these days is a wholesale market, which means it exists to make sales to other institutions such as restaurants, hotels, or your local highstreet butcher. Businesses such as G Lawrence Wholesale Meat Company Ltd operate from inside units within the old Victorian market building, selling their meat between midnight and 7am, Monday to Friday. Despite recent inflationary pressures, these wholesalers are high-volume businesses that can be wildly profitable, with the top ones able to make millions of pounds of profit a year.

Lawrence, who has seen enormous change as the market’s role changed during his career, said the physical face-to-face element is what makes Smithfield tick: “Good butchers still like to come up the market and pick their lambs out, pick their pigs out. The old saying in Smithfield is ‘let your eyes be the guide’.”

Unusually for a wholesale market it is open to members of the public, who are able to walk in and make a purchase at far cheaper prices than they’d find anywhere else on the high street. The only catch is they need to get up in the middle of the night to do so. This nocturnal lifestyle, along with Smithfield’s own language (some staff are called called bummarees, for reasons lost to the depths of time), has given the market a mystique beyond its reality — such as the oft-repeated talk of pubs that serve pints at 6am for the post-work butcher crowd. Rather than establishments overflowing with rowdy butchers at dawn, nowadays you’re more likely to see a handful of office workers ordering a coffee.

(A nuanced picture of Smithfield can be see in the brilliant 2012 BBC documentary The Meat Market, inexplicably not available on iPlayer but pirated on YouTube.)

Lawrence blamed congestion charging as the thing that had the biggest effect on the market’s culture during his time working there, as it pushed suppliers and buyers to do their trading in the middle of the night in order to avoid paying the fee. Staff, who these days tend to drive in from Essex and Kent, dash home at the end of their shift to avoid the £15 fee rather than stick around for a post-work pint: “In our trade we’ve beaten foot and mouth, mad cow disease, we’ve overcome everything. But we couldn’t overcome the congestion charge. We had to start earlier and earlier. The hours now are horrific. When I first started you began work at four in the morning. Now you start at ten at night.”

At one point central London had four big London wholesale food markets — Covent Garden and Spitalfields for fruit and vegetables, Billingsgate for fish, and Smithfield for meat. One-by-one they have all relocated further out of the centre since the 1970s, with Smithfield the last one standing in its original location.

The area has changed enormously in the last decade alone. At one end of the meat market is now an entrance to the Elizabeth line, the multi-billion dollar railway offering direct trains to Heathrow and Canary Wharf. Proposals to demolish the neighbouring (and long defunct) Smithfield general market site were defeated after a decade-long battle and the building will now be used as the extraordinary-looking new site for the Museum of London.

Yet while the press coverage has talked about the end of Smithfield, for Lawrence he’s clear it’s just the end of the current site, rather than the service it provides. Even if the City of London isn’t leading on the relocation, the money they are providing to the wholesalers as compensation will be used to set up a new market.

Lawrence said: “Smithfield will carry on elsewhere. This is a guarantee. 100%. We’ve got to think about food security, we serve all of London, prisons, hospitals, care homes, universities, as well as the butchers and hotels. Smithfield Market couldn’t close up and disappear as it would put people in jeopardy.

He also insisted the annual meat auction will continue at the new site and revealed the name of the future location: “It will be called ‘New Smithfield’.”

“I can’t declare too much on that because otherwise the people we’ve been dealing with might put the price up. We’re doing it collectively with the other wholesalers but they [the City of London] will give us any help they need.”

A spokesperson for the City of London said they were "continuing to work with and support traders, ensuring they have the financial support and guidance they need to transition seamlessly to locations of their choosing".

Yet for now Lawrence is focussing on organising this year’s event. He’s got simple advice for first-time attendees of the auction, as he prepares to sell off “tens and tens and tens of thousands of pounds” worth of meat in little over an hour: “You need to turn up and have plenty of money with you. You pays your money, you takes your chance.”

He added: “Some people go up there not having decided what they’re going to have for Christmas dinner until they see what they can get at the auction. I think that’s a great way to live! I think it makes it a bit more exciting, I wish my wife would do that.”

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please forward it to a friend. London Centric has no corporate owners and relies on word-of-mouth for distribution.

Have something to share? Please get in touch over email or WhatsApp or leave a comment.

You write brilliantly Jim, there's still hope for you youngsters!

Great stuff yet again, Jim. I enjoyed reading his slightly more optimistic view of the move than I’ve read about elsewhere.

Also delighted to see another fan of that documentary(!). Such a great series - the Billingsgate episode was fascinating too.