Kitchen foil and Algerian markets: What happens when your phone is stolen in London?

Plus: Fake Forrest Gump-themed shrimp restaurant payout — and pub survives licence review after drinkers disrupt a child's music practice.

There was a lot of coverage of this week’s London Centric story on Lime bike safety, with ITV London running the reporting on its evening bulletins and national news outlets following it up. London Centric’s own documentary about the subject is now available to view on YouTube.

London Centric’s growth was profiled in the New Yorker this week, while some of our recent stories were also discussed on the Open City podcast. All of this is only possible with your support, so thank you.

Today, we’ve got a fascinating guide to the capital’s newest version of phone theft, phone snatching, by writer Conrad Quilty-Harper, the founder of the Dark Luxury newsletter.

Londoners are familiar with the moment your phone gets snatched, usually by a man on an e-bike, but what happens to it once it has left your hands? He reveals how Algeria is starting to rival China as the likely destination for your stolen device — and how thieves are using kitchen foil to avoid police detection.

Scroll down to read the main story.

Exclusive: Billionaire Prince Charles Cinema landlord settles claim he ran illegal Forrest Gump shrimp restaurant.

Asif Aziz, the billionaire landlord at the heart of an ever-growing number of London Centric stories, has paid £150,000 to settle allegations he illegally ran a fake Forrest Gump-themed shrimp restaurant at Piccadilly Circus.

Paramount Pictures sued Aziz personally, claiming he and his companies infringed the trademarks of Bubba Gump Shrimp Co, a franchised restaurant chain based on a crustacean-loving character from the 1994 Tom Hanks film.

Aziz is best known to London Centric readers for his attempts to “bully” the Prince Charles Cinema and for his cockroach-infested housing in Croydon. He also owns the Trocadero building in the heart of central London, which made him the longterm landlord of two central London restaurants aimed at tourists that used licensed trademarks: Bubba Gump Shrimp Co and the jungle-themed Rainforest Cafe.

At their peak, the lawsuit said, both Bubba Gump and the Rainforest Cafe were bringing in revenue of up to £450,000 a month. But when the pandemic hit in 2020 the franchised restaurants went bust, leaving Aziz with empty units and no rental income.

Paramount and its fellow claimant, the US branded restaurant chain Landry’s, alleged that Aziz’s response was to surreptitiously infringe their trademarks by illegally reopening the Bubba Gump and Rainforest Cafe venues using his own staff without their permission.

It was alleged that Aziz and his Criterion businesses continued to operate the restaurants with tweaked variations of their old names but the same interior, while providing a substandard food service and hoping tourists didn’t notice the change. As part of this he was accused of “passing off” by operating a cafe called “Jungle Cave” using the Rainforest Cafe’s distinctive interior such as “Jenny the Banyan Tree, a large anthropomorphic sculpture of a tree”.

In his defence, Aziz argued he isn’t in day-to-day control of his companies and both the rainforest and Americana are generic themes for a restaurant. Both sides reached a confidential settlement to avoid the case going to trial. But at a court hearing last month, attended by London Centric, a judge was told that Aziz and his companies had paid hundreds of thousands of pounds in damages and legal costs to settle the case.

The landlord’s property ownership and wealth is obscured behind a complicated series of off-shore trusts in tax havens, denying Londoners the ability to know how much of the city he controls. Yet Paramount told the court Aziz remains deeply involved as a “shadow director” of the property companies and appeared on video calls.

When Aziz’s fake Forrest Gump restaurant finally shut down, his company needed to find another tenant for one of central London’s most prominent shop units. The shrimp restaurant was refitted and became the tax-avoiding fake Harry Potter shop featured in December.

London Centric will, with your support, have much more to report on Aziz in the future.

London Centric is funded by its readers. If you want to take a stand against clickbait journalism, fund original investigative reporting about the capital, and receive members-only investigations then please considering subscribing.

Pub survives following claims drinkers were disrupting neighbour’s “music practice”.

The Sekforde in Clerkenwell has survived with its licence intact, following noise complaints against the Victorian pub. It’s just the latest round in an ongoing battle between London’s drinking establishments and the people who have bought expensive houses next to them.

Footage recorded at a council meeting by student journalist Pablo Edward shows a local resident spelling out their objection to the noise made by the pub’s drinkers: "The impact on my family has been devastating… My son was only a small baby when the pub reopened, he’s grown up surrounded by screaming, shouting, swearing. Our bedtimes have been disrupted. Can you imagine seven o’clock? His homework? His music practice? We’ll never ever get that time back.”

Another individual at the council meeting offered a different view, saying that her goddaughter and her family had lived near the pub for twenty-five years and “never once complained about noise or nuisance”.

P-p-pick up a London Standard, win a car.

Journalists at Lord Lebedev’s London Standard received an email this week requiring them to urgently send suggestions to management on how to build “even more enthusiasm and awareness” around their weekly newspaper.

“The print produce [sic] is looking fantastic, but we need to do more to drive visibility, pick-up, and engagement,” said acting editor Anna van Praagh. “Should we give away an electric car, for example, or a flat in a new build or are there competitions or brand partnerships we could run to build excitement? Should we be stocked at football stadiums, or at concerts at the O2, or Wembley?”

London Centric, sadly, remains unable to offer such inducements.

What happens when your phone is stolen in London?

By Conrad Quilty-Harper

In some of the darker corners of the internet and the most brightly lit corners of the British media, you could easily believe that you can’t walk down a London street without someone stealing your phone from your hand. Phone snatching is an increasingly ubiquitous part of life in the capital, even if many Londoners are slightly non-plussed by anxious queries on tourist forums about whether it’s safe to bring your mobile phone on a visit to the capital.

As crimes go, it’s defined by its swiftness – a quick blur of an e-bike that barely registers in your peripheral vision and a sudden grab before you have a chance to realise what’s happening. But the crime goes far beyond that momentary interaction, both in the hours of inconvenience it causes to the victim and the long journey that follows for the stolen device.

Like 115,000 other Londoners last year, my phone was stolen. I was walking along High Holborn outside the Rosewood hotel when two men wearing black and riding along the pavement on e-bikes snatched my brand-new iPhone out of my hand. Moments earlier they had taken a fellow pedestrian’s phone, earning as much as £400 for a few seconds’ work.

On the same day I was mugged there were 270 phone thefts reported to the police, according to a Freedom of Information request. On average just two percent of those stolen phones find their way back to victims.

Like so many relatively non-violent crimes the hassle involved renders it unlikely the victim will want to prolong the experience. Perhaps you report it to the police to get an incident number to give to your insurance company. Or possibly you try to “brick” your device, stopping all services, before working out how on earth you can afford to replace it.

But once you’ve moved on, vowing to keep your eyes up while you walk around London, what happens to your phone?

A complex global distributed criminal network, propped up by hundreds of thousands of Londoners’ personal devices, has evolved to efficiently extract the maximum value from each device – and to satisfy insatiable demand across the world for second-hand phones and their parts.

Step one: The snatch, the illegal e-bike, and the tin foil.

Phone snatchers previously used stolen mopeds, which had the downside of being both loud and having an easily-trackable numberplate. These days they increasingly rely on e-bikes that can travel at speeds of more than 30mph. These vehicles are illegal to ride on public roads but can be easily bought in the UK on the proviso they are only for riding off-road on private land. In reality, many of them are used for illegal purposes on the streets of major cities.

Inspector Dan Green of the City of London police, which looks after the capital’s financial district, said a typical phone is worth between £100 and £200 to a thief: “They can easily get 20 phones in one sitting. They can make a few thousand in a morning’s work.”

Sometimes riding in pairs, the phone snatchers often travel on loops along familiar routes around the capital, riding up on the pavements and grabbing devices out of users’ hands.

Green said that a couple of years ago his “proactive acquisitive crime team” were having a lot of success tracking down stolen devices to shops and houses using tracking features built into phones.

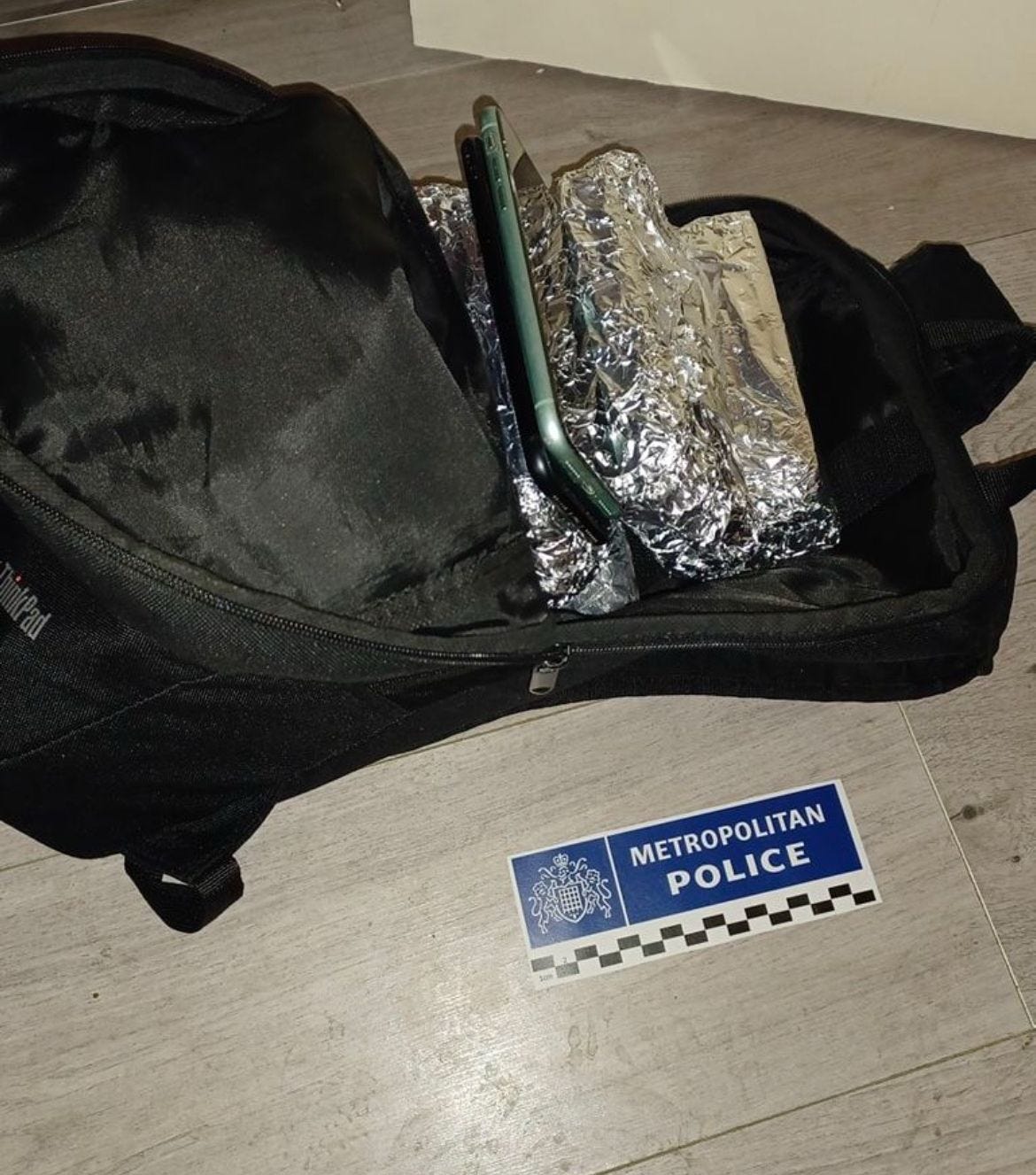

These days, he said, “tracking options are getting fewer” as thieves have got smarter. Now, as soon as they grab a phone from the hands of an unsuspecting individual, they tend to put it into airplane mode or into a metal wire-lined faraday bag which blocks the device’s GPS and phone signal. Less professional thieves wrap them in kitchen foil. Others are dumped in a bush waiting for someone else in the criminal’s network to pick them up.

The police officer said: “Our phone snatchers go offline really quickly. We’re losing where they’re going from that point onwards.”

Step two: The phone is flipped to a fence.

Green explained that, while some thieves try to grab unlocked phones and empty a user’s bank accounts, the typical e-bike rider is not operating at the sophisticated end of the industry: “They want the handset and they want it offline and they want to sell.”

In many cases thieves use public transport links such as the Victoria line and Elizabeth line to move phones from the scene of a theft in central London to distribution hubs in Finsbury Park and Stratford as fast as possible.

The phones are then offloaded to a “fence”, a criminal who pays cash for goods and may have more nefarious intent. One Algerian gang based in London was recently jailed after being found to have handled more than 5,000 stolen phones, first trying to gain access empty bank accounts then shipping the phones abroad for parts.

As with any enterprise – criminal or other – that springs up in London, a thriving service industry has grown around the stolen mobile phone supply chain, including companies who can offer solutions to bypass Apple’s security. London-based iRemoval Pro Ltd, is one of many companies which offers an iCloud bypassing and iPhone unlocking service, charging as little as $85 (£65) per device.

iRemoval Pro claims on its website to have unlocked over 300,000 devices as of 2021, suggesting it could have made tens of millions in sales for its UAE-based founder Hichem Maloufi, whose Instagram chronicles a life in first class suites and on private jets. Despite appearing to be a very healthy business, iRemoval Pro Ltd is listed as dormant on Companies House with just £1 of assets in its most recent accounts.

On a visit to iRemoval Pro Ltd’s London-listed address, I found a serviced office that caters to tens of thousands of businesses. The receptionist behind the front desk offered to pass on a message to Maloufi. He has not responded at the time of writing.

Step three: Bye-bye London! The phone heads abroad.

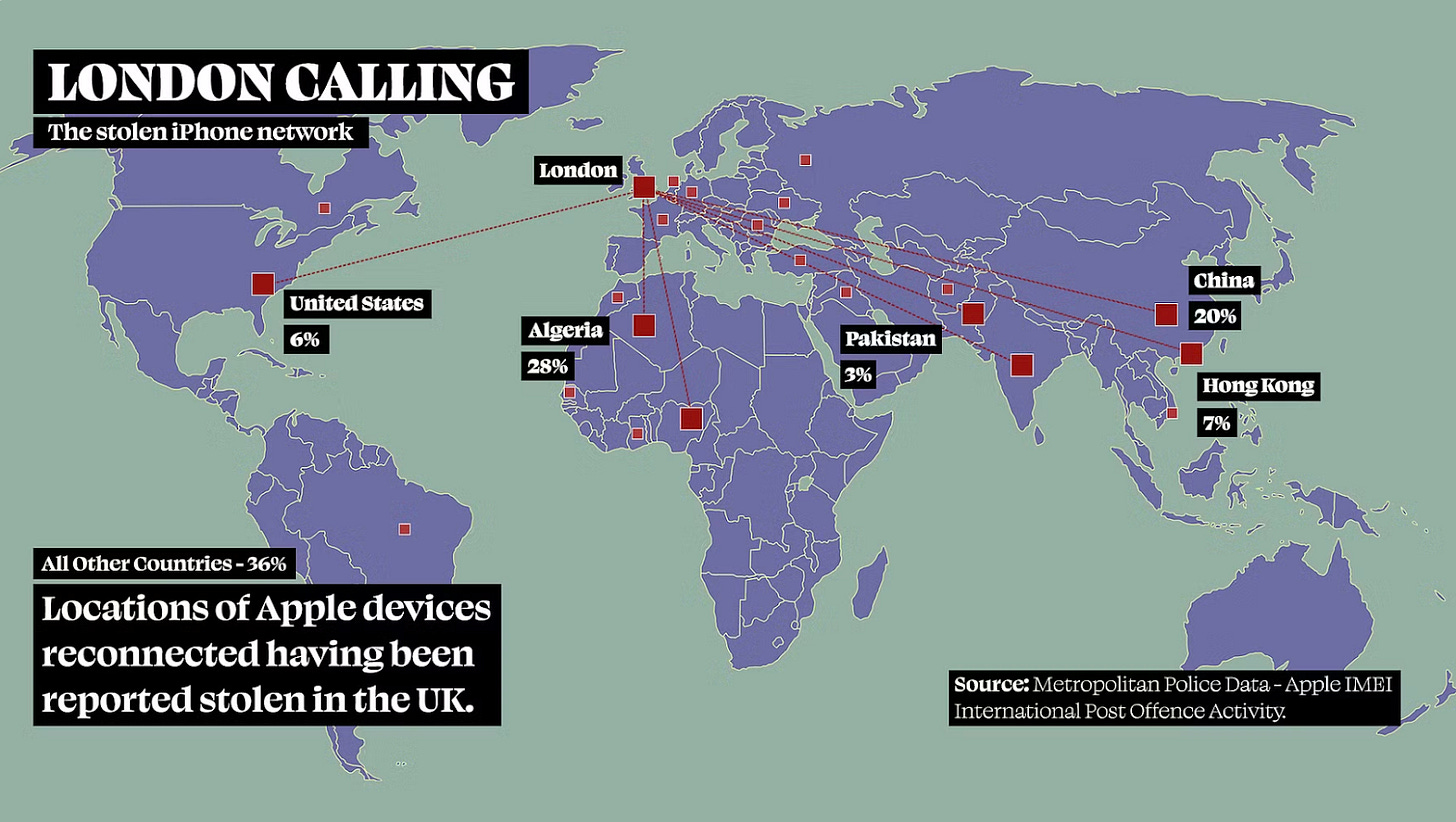

If efforts to unlock the stolen phone fail in the UK the fence will likely sell the phone on to someone who will break up the phone for parts. I spent weeks watching my iPhone move across the globe on my Apple account. It travelled thousands of miles to Hong Kong, then to Shenzhen in mainland China, and finally ended up in a department store in Moscow where the tracking stopped.

Zituo Wang, a PhD student at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, told London Centric that China is the key to understanding why the criminal trade in stolen phones exists as it combines demand for second-hand phones with the expertise to break them into parts.

Every year as many as 100 million phones, many of them stolen, are imported to Shenzhen, just north of Hong Kong. Smugglers go to extraordinary lengths to get them across the border from Hong Kong without alerting authorities. Wang’s research, based on China’s border data, revealed the use of thousands of human mules (they’re called “water travellers” in China). One group of smugglers used drones to drop zip wires and transfer up to 15,000 phones over fences at night.

Shenzhen’s Huaqiangbei market, the world’s largest electronics market, is “the node to handle everything related to phones in the global criminal network”, according to Wang.

Multiple floors full of iPhones and other models are available to buy, with every component of every model being available. With iPhone manufacturer Foxconn just down the road, along with at least 40 other suppliers of parts for Apple, the city is an unparalleled source of expertise for people who are trained in breaking down iPhones for parts — because many have helped build them in the first place.

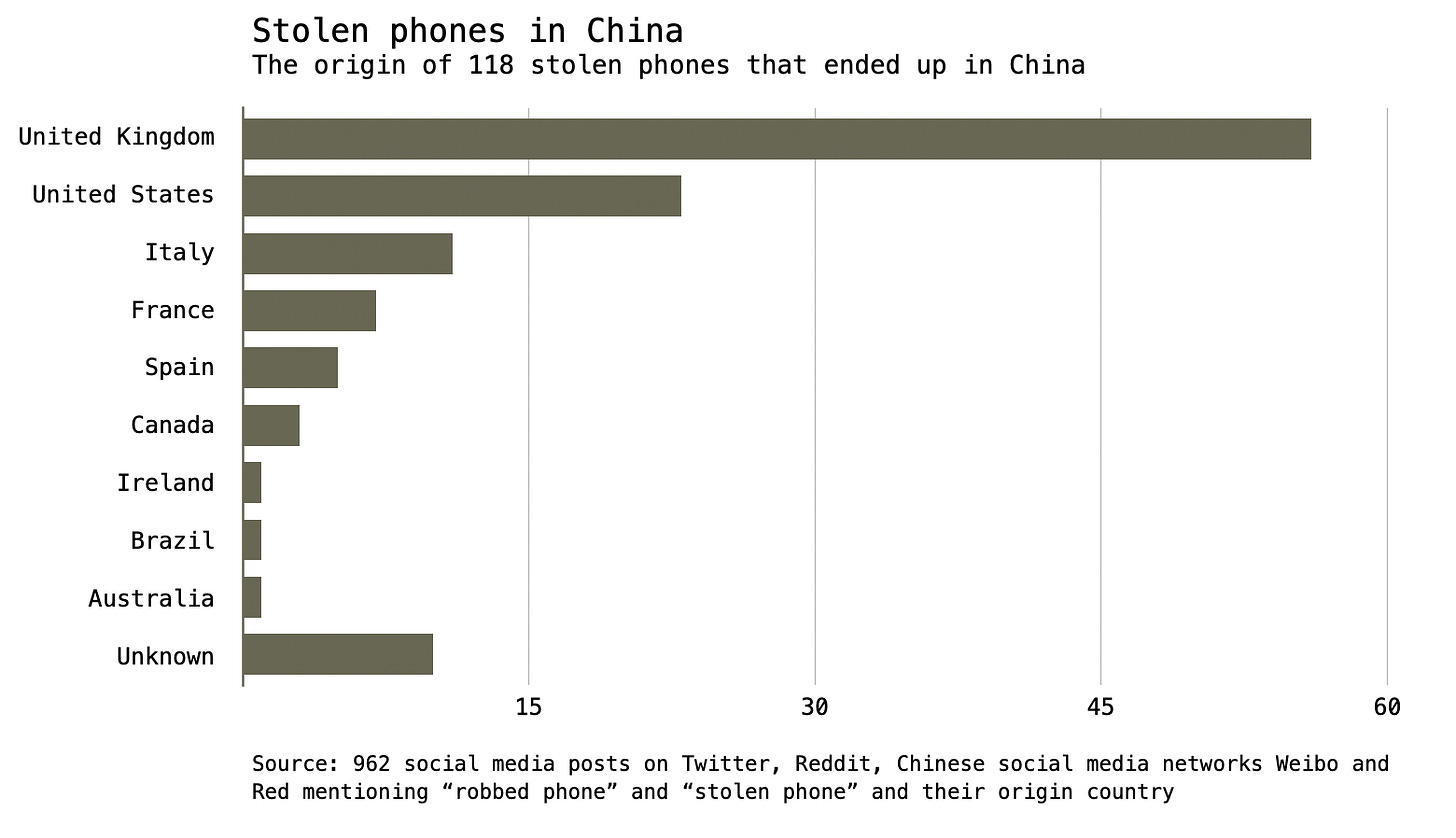

Britain (and therefore London) is one of the primary sources of these stolen phones, according to Wang’s research. Using data scraped from social media in both the West and China he found that the most common origin of reports of robbed or stolen phones being located in China was the UK.

But China is facing competition from North Africa, with a Metropolitan Police survey of 4,000 stolen iPhones at the end of last year finding that 28% of phones taken in London end up in Algeria where there are busy markets selling stolen devices.

Stage Four: Intimidation and a final attempt to unlock the phone.

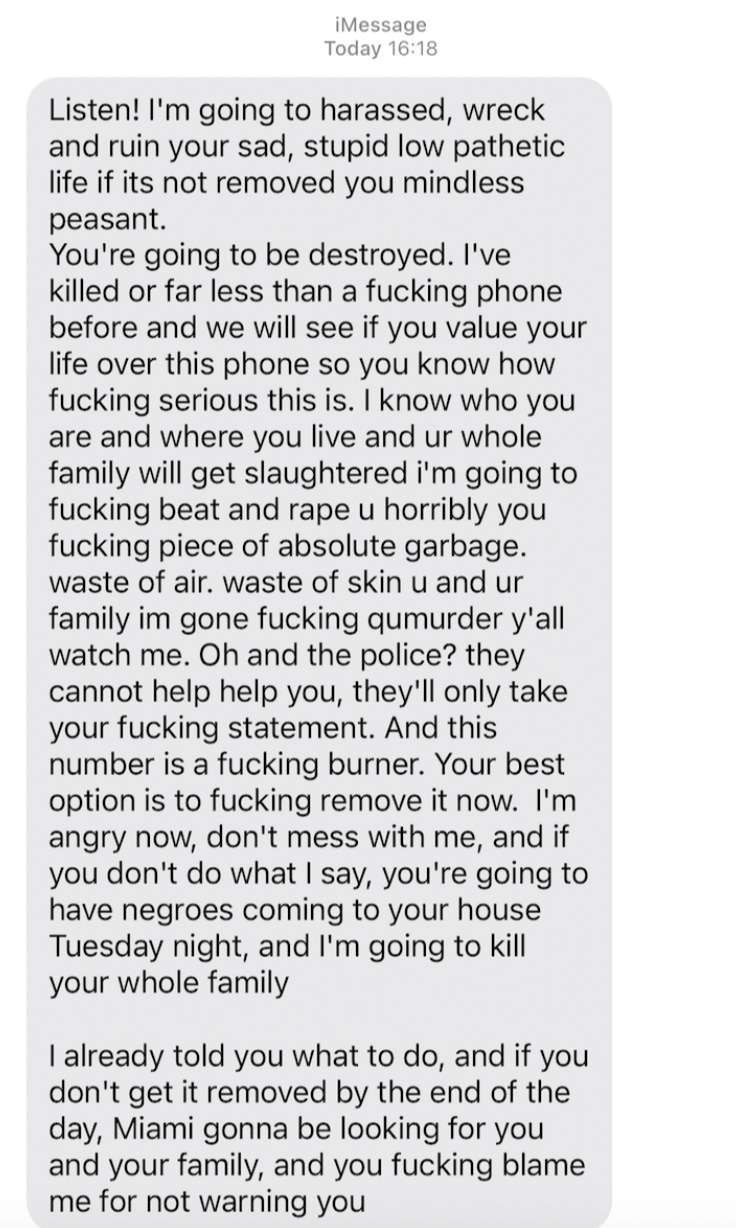

After my phone arrived in Hong Kong, I started receiving threatening messages telling me to remove the lock on my stolen iPhone, including a video of someone waving a gun and a screenshot of my iCloud account. If I could be convinced to unlink the stolen phone from my Apple account then the phone could be wiped and resold it for its full value on the second hand market. Otherwise, it would have to be broken up for less valuable parts.

The highly templated messages I received, which are almost identical to dozens of other messages I saw on Reddit and Apple’s support forums, suggest that they might have been using what’s called crimeware-as-a-service. In effect, this is a piece of software developed by criminals to try and automate the process of sending threats and make the criminals’ lives easier. These text messages included pledges to kill me, engage in sexual violence, and racist terms.

If those threats don’t work criminals might also try using phishing techniques. Some victims receive very convincing but fake iCloud login pages to try and trick users to enter their password.

What’s the solution? Technical changes by the phone manufacturers and tougher policing.

Phone thefts have been one of the biggest single crimes in London for years, and the rate in London is 22 times the national average, according to Crimerate, a website which analyses official open data about crime data rates.

Traditional policing methods clearly aren’t working argues Wang, the researcher in Los Angeles.

He suggested international blocking of unique phone identifier codes (IMEI) which phones use to access mobile networks – many countries, including the US, do not legally require IMEI blocking of stolen phones. More radically, Wang suggests basic information about stolen phones should be shared publicly, with the victims’ permission, to create a global database of robbed and stolen phones. This would enable international police forces to more effectively collaborate, and generally “create more burdens for the criminals”.

Green, the City of London police officer, said his team were encouraging people to add identifying stickers to their phones because newer iPhone models don’t even have the unique IMEI number printed on on their SIM card tray: “We’ve recovered possibly a thousand mobile phones over the last two years and returned less than half. We can’t find the victims.”

He also highlighted the case of prolific phone snatcher Sonny Stringer, who went viral when the City police released footage of their officers using a car to ram him off his e-bike.

“That arrest had quite an impact on the [phone theft] numbers for the following month,” said Green. “Taking him out was significant but it also sent out a message: Come into the City and there’s a good chance you’re going to get knocked off your bike.”

“They’re expecting us to try.”

The reaction from the police when a Londoner asks about an individual case of a stolen phone is often one of indifference. The crime is particularly infuriating in the cases where the phone can still be tracked, as the victim helplessly watches their device move from the capital to locations around the world.

When I tried to find my stolen iPhone, one second hand phone shop in central London said they’d also been the victim of thefts — and claimed the nearby Charing Cross police station sometimes has to create a separate queue for phone thefts because there are so many snatched, particularly during the summer months.

This was denied by the Metropolitan police officer working behind the perspex screen at the station. I asked for her to check for an update on the progress of finding my lost iPhone, last seen in a Moscow department store, according to my iCloud account. “We don’t give out updates,” she said.

Green said his much smaller group of officers at the City of London police are able to take a more personal approach, even if the result isn’t different: “One of my team will give you a call and explain we’re at least trying to do something. When I speak to victims they’re not expecting to get property back, they’re expecting us to try.”

Did you enjoy this edition of London Centric? Please forward it to a friend, get in touch via email or WhatsApp, or leave a comment.

Thrilled to share this story with you all alongside a headline containing the words "illegal Forrest Gump shrimp restaurant."

Standing on my soapbox in the comment section to implore people to do small things to protect their data in advance should they fall victim to phone theft (my instructions will be iPhone-specific but I'm sure there are comparable Android functions that could be found with a light google):

[1] Make nothing accessible from your Lock Screen when locked! [Settings > Face ID & Passcode > scroll down to 'Allow access when locked' and turn everything off, but esp. Control Center] If a thief can't access the control panel without a password, then they can't turn your phone on Airplane mode, which means you have time to get back to your laptop and put the iPhone on lost/stolen mode.

[2] If, either by snatching your phone when it's unlocked or otherwise unlocking it, they will try to change your phone password so they have master control. Change your setting so that any password change requires an hour's delay! [Settings > Face ID & Passcode > scroll down to 'Stolen Device Protection' and turn On]. (Again, the goal being: get time to get to your laptop and put it in lost device mode)

Admittedly both things make some day-to-day actions slightly more tedious. But if you have insurance, losing the hardware is survivable. What you don't want is them getting into your bank accounts or e-mail or locking you out of your phone before you have the chance to protect your data.