How to catch a London bike thief

Plus: Sadiq Khan's winter homelessness conundrum and a £5m cottage in Dulwich.

There’s a good rule that news reporters should try to follow: Don’t let yourself become the story. Unfortunately, sometimes the story is thrust upon you. In recent weeks I’d been working on an investigation into London’s bike theft epidemic, hoping to understand the mentality and methods of the thieves operating all over the capital. Then, on Friday afternoon, my own bicycle was stolen from outside my house.

What came next was a long and exhausting – if fascinating – lesson in how the London bike thief thinks and operates, how the Metropolitan Police (won’t) help even when you’ve tracked down the building containing your stolen property, and an unexpected tale of how to catch a criminal in the act.

But the personal element is almost irrelevant: What today’s main story reveals is a London guarded by a cash-strapped police force where certain types of crime are now effectively legalised — and where sometimes the only way to get your belongings back is to do it yourself.

Scroll to the end to read the story — or first enjoy the London Centric Bits

A massive thank you to everyone has signed up to London Centric so far. Last week I took part in a Reddit AMA to answer questions about my hopes and fears for this outlet.

A growing number of you have been kind enough to take the plunge and become paying members in order to support original local journalism in the capital. If you’re still hesitating, please do subscribe – there are some big subscriber-only stories coming up in the coming weeks.

Exclusive: Did Sadiq Khan’s City Hall try to cut funding for emergency homeless shelters?

Sadiq Khan convened an emergency homeless summit last Tuesday, as new figures show that 4,780 people are now living rough on the capital’s streets, a substantial rise on last year. The mayor warned that the issue will get worse before it gets better, while also pledging even more funding towards his re-election promise of eliminating rough sleeping in London by 2030.

A day later, sources in the capital’s local government world got in touch to express their surprise at the mayor’s public intervention. They had told London Centric that Khan’s Greater London Authority was in fact in the process of radically cutting the funding available this winter for a network of emergency homelessness shelters.

The Severe Weather Emergency Protocol — known as SWEP — sees London’s 33 local councils open heated buildings for rough sleepers when the temperature drops beneath freezing, minimising the risk of death on the streets from hypothermia. For many years the Greater London Authority — the overarching pan-capital organisation run by Khan — has coordinated the plan and spent well over £1m every winter providing “overflow” accommodation. This provides additional space for rough sleepers when an individual London council runs out of rooms, ensuring there is always a back-up option available.

Yet last month the boroughs learned that City Hall was planning to drastically cut the funding for overflow spaces this winter, leaving councils to pick up the slack. With local government finances in a state of collapse, the councils feared the worst.

The official line from Khan’s team is that no final decision was ever made to cut the City Hall funding for overflow spaces. The unofficial line, according to sources, is that there was a sudden reverse ferret after London Centric began asking questions about the cut and City Hall realised how the decision would be portrayed in the media.

A spokesperson for Khan confirmed the central funding for overflow accommodation for rough sleepers during freezing weather would now be maintained for another year: “As you’d expect, the GLA and London Councils frequently have strategic discussions about how they can work together more effectively to help rough sleepers off the streets. The Mayor is absolutely committed to doing everything in his power to address the scandal of homelessness in the capital.”

Preposterous London property of the week.

While London’s rough sleepers hope there’s space for them this winter, some other residents of the city may be in a position to spend £5m on this three-bed house in Dulwich Village, the Hampstead of south London. (Or at least that’s what its residents would like you to think.) Just don’t be taken in by the list price. When you reach this price bracket on a three-bed, the name of the game is knocking down and rebuilding. Neighbours should expect to ultimately see something substantially bigger on the site, with new owners able to wander down to Gail’s Bakery and talk about how they live “a village life in Zone 3”. The area was briefly home to Margaret Thatcher, who moved into 11 Hambledon Place, a nearby mock-Georgian Barratt Home, after leaving Downing Street in 1990.

Who is going to be the Conservative mayoral candidate?

London Centric’s first edition, published before many of you signed-up, looked at some of the potential candidates for Labour’s mayoral candidate in 2028 if, as is widely expected, Sadiq Khan steps down after three terms. Now the Conservatives are getting in on the speculation game. With few in the Tories optimistic about a return to national government at the 2029 general election, standing as the Conservative candidate for mayor of London is starting to look like one of the best (and most high-profile) opportunities in the party.

The names are starting the swirl around. Will Tory London Assembly member Neil Garratt stand? Or perennial candidate Andrew Boff? What about James Cleverly, a man whose career started at City Hall and stalled after he lent too many votes to the other candidates in the recent Tory leadership race? The other rumour is that ex-MP Penny Mordaunt may be getting tired of the commute from Portsmouth. I’m all ears if anyone wants a chat.

“That’s up to you”: How the Met Police washes its hands of bike theft.

James Dunn, the founder of bicycle recovery service BackPedal, wasn’t expecting a call from me on a Friday evening. We’d spent weeks discussing how best to investigate the plague of bike theft in the capital for a London Centric article. I’d tried knocking on the doors of convicted bike thieves after they got out of prison but, strangely, the criminals didn’t want to share all their tactics with a journalist. I’d asked to accompany Dunn’s recovery agents as they track down and retrieve client’s bikes, using GPS trackers they hide on the frame, but we hadn’t yet scheduled in a date.

In desperation, I’d bought a cheap bicycle with the intention of using it as “bait bike”, a tactic used occasionally by the police to smash organised gangs. Dunn’s company was going to fit my new purchase with a specialist tracker, wait for it to get stolen, then we’d see where it ended up.

Instead, I’d accidentally jumped the gun.

Earlier that day I’d left my family’s electric cargo bike outside my home while dashing in for a Teams meeting with a group of London council communications directors. The battery-powered bike can carry two children across London faster than public transport and is far cheaper than owning a car. Every story in London Centric is reported from its saddle, as I cover hundreds of miles across the capital every week in search of news. It has transformed my life. But, as the thieves who must have been watching my house knew, it is not a cheap bit of a kit. And by the time I went back outside, it was gone.

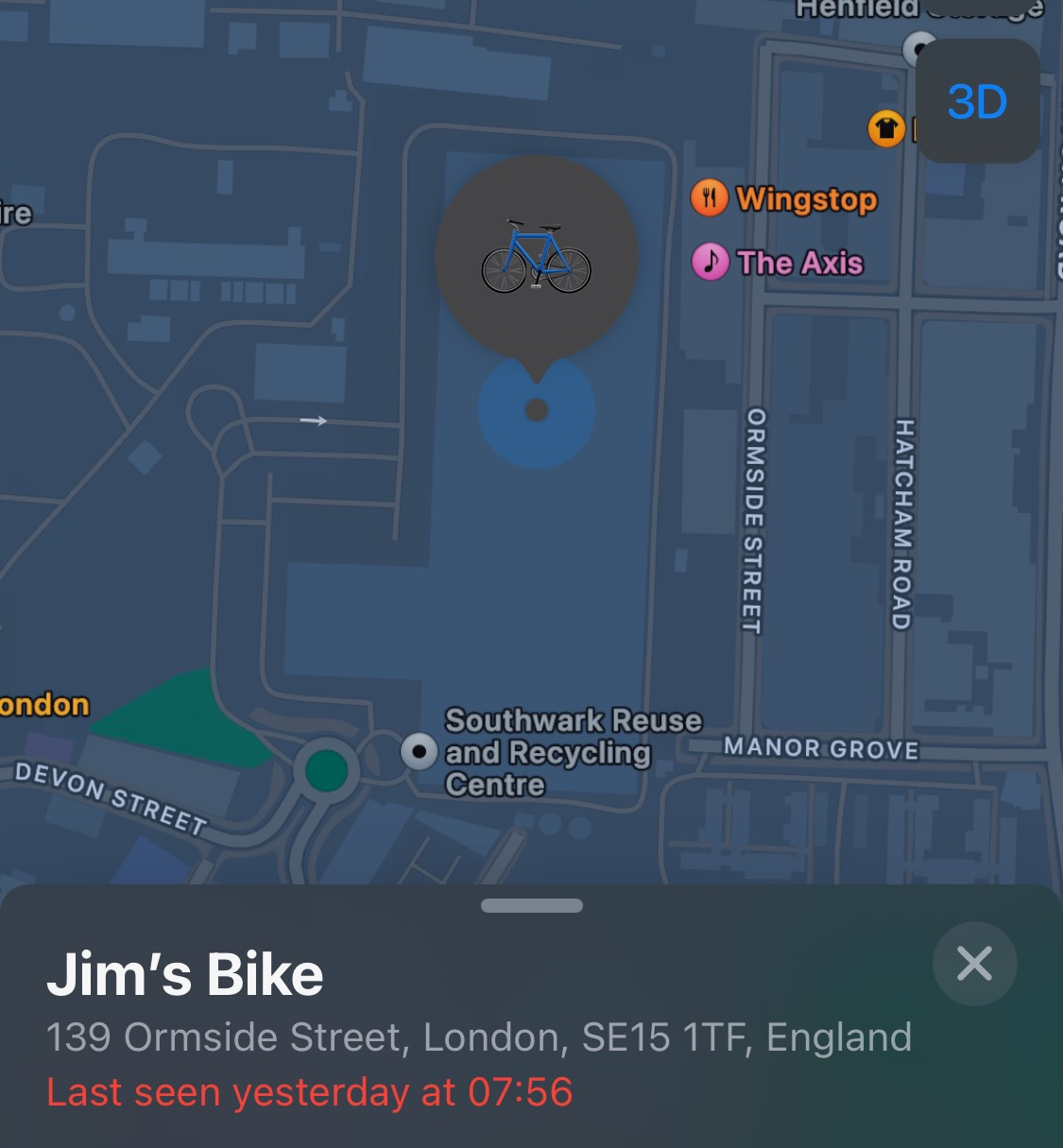

“This honestly wasn’t the plan,” I told Dunn, desperately trying to make light of the situation. The son of a policeman, Dunn reeled off tips on what do if I wanted to see my bike again, explaining that it was probable that I was being watched and he would expect such a heavy bike to be kept in a ground floor flat. But he tried to emotionally prepare me for the worst: the likelihood was that it was gone forever, with my best chance being that the insurance company might pay out. All my hopes relied on a £28 Apple AirTag that I’d hidden in the bike’s frame. The basic tracking device would ultimately end up being the only reason I got the bike back — but it took hours of detective work, a lot of luck, and a sprint across the streets of London to confront a thief.

If you want to understand the scale of London’s bike theft problem then you need talk to the man who pays out when it happens. Tobias Taupitz is co-founder and CEO of bike insurer Laka. Under its pioneering co-operative model, all customers pay a fluctuating amount based on their share of theft claims — and over the last year those payments have shot up for Londoners.

His company has split the UK into three distinct categories to assess the risk of theft: “Rural”, “Urban”, and “London”. It doesn’t take a genius to work out which is worst.

“The theft rates in London are significantly higher than we would expect,” said Taupitz, who warned that certain types of bicycle could soon become uninsurable in the capital without proper enforcement from the authorities.

“Thieves have learned to monetise the bikes much better,” he said, suggesting an increasingly professional operation. He suggested a major issue compared to other cities is the way London’s cycling culture is driven by the wealthy wannabe-Tour-de-France middle-aged man in Lycra riding expensive racing bikes and families buying e-bikes: “The average bike has increased in value a lot. You used to have your £200 bike that you would barely lock and now you have £5,000 bikes.”

At the same time, London’s housing stock means that many people don’t have the space to store their bikes inside — meaning these increasingly expensive items are left outside homes or in communal cycle storage areas. With even pricey D-locks vulnerable to a mobile angle grinder in the space of a minute, there’s little to stop a determined thief. Some customers are upgrading to angle-grinder resistant locks that cost £250. In response, thieves are cutting apart the metal stands that the bicycle is attached to — and cycling the bike off with the lock still attached.

Taupitz said GPS tracking devices offer hope but there are signs that criminals across Europe are adapting fast: “Thieves are loading entire cargo bikes into refrigeration units so it blocks the signal to trackers and gives time to dismantle them. There’s even been reports of thieves who fit a trackers to a bike, then sell the bike and steal it again.”

One of the toughest aspects of trying to understand bike theft in London is that everyone is relying, to varying degrees, on guesswork. There’s limited academic literature on the operations of the bike thief. With few prosecutions, there’s also few court cases where thieves’ tactics are revealed. And most people — and the police — simply give up hope the moment that a bike goes missing. Some thefts are clearly highly targeted, such as the muggings of cyclists on high-end bikes in Regent’s Park. Others are opportunistic joyriders. Many are somewhere in the middle.

Dunn, from BackPedal, said his biggest customers are food delivery companies with large in-house e-bike fleets. These businesses operate around the world but haven’t seen anything like what goes on in London: “They refer to the UK as ‘The Jungle’ because of the theft rate. Fundamentally, if you think about it from a thief’s perspective, bikes are good things to steal. You don't have to break into people's houses to steal them and they’re usually out somewhere risky.”

While there’s still debate over who makes up the bike theft community, there’s two things that people in the industry agree one: First, that the lack of enforcement by the Met police makes bike theft a low-risk, almost legalised, criminal activity. And second, that Facebook Marketplace and Gumtree are the lifeblood of the bike theft industry in London, providing the ready supply of people willing to spend hundreds or thousands of pounds on a dubiously-sourced secondhand bike.

Dunn said: “If there was one thing that would stop theft, it would be a total shutdown of the secondhand bike market. But obviously that's not possible or even something you'd want anyway.”

As soon as my bike was stolen on Friday, I phoned the police to report the theft, not least because any insurance claim requires a crime incident number. It immediately became apparent that the Met Police, weighed down on a Friday evening with a huge number of other calls, did not want to get involved. They issued me with an incident number and told me that I would get a call back within two days – a call I have yet to receive. When I said an AirTag was tracking the bike and it was still in my local area, they advised to call back if I tracked it to a precise address.

Apple’s AirTags work in two different ways. First, they use Bluetooth signals to ping off any Apple devices in their vicinity, even if they’re owned by other people, sharing approximate location details with the owner of a missing item. This then appears on Apple’s “FindMy” app, with varying degrees of accuracy based on how many other devices are in the area. Or, if you’re the owner of the AirTag and you get your phone very close to the tracking device, you can lock on with ultra-accuracy — usually displayed as a floating arrow on an iPhone screen guiding you on the final few metres. They are an imperfect solution for bike theft, not least because Apple’s built-in anti-stalking measures make it easy for a thief to be alerted that they’re being followed.

After two hours of wandering around my local area, I had a pretty good idea of where my stolen bike was being stored. One corner of a mid-sized block of flats close to my home was regularly emitting a signal from the bike’s AirTag. A friendly resident let me inside and I called back the police, as they had suggested, to see if they would send back-up to help me recover the bike.

“Is it a block of flats? We do not attend when it’s a block of flats,” they said, explaining the police could not spare the time trying to retrieve stolen goods in a building with multiple floors. The conclusion was clear: If you’re going to have your bike stolen with a tracker attached, and want the police to intervene to help retrieve it, then make sure the thief lives in a detached house with its own front door.

“Would you attend if there was an emergency?” I asked, with the potential threat of violence from unknown thieves in mind. The police operator confirmed that they would. I said I was going to attempt recovery on my own. “That’s up to you,” they said.

Dunn founded BackPedal during the pandemic after his partner’s bicycle was stolen and they realised, despite obtaining CCTV of the incident, that there was no way of tracking down the thieves. After paying a £129 installation fee for GPS devices, BackPedal customers are charged £7.49 a month for ongoing membership of the scheme. Once a bike is reported stolen the service kicks in to gear, with a team at HQ directing a group of freelance recovery agents, whose numbers include ex-policemen, security staff, and even a former member of the Bulgarian border force.

Dunn says his agents retrieve about 30 stolen bikes a month, with an 80% success rate. Bodycam footage of their recovery is then posted online, with almost all bikes willingly handed over without confrontation: “Every time you get a story about how ‘my son brought this back last night, he didn't tell me this was stolen’ or, ‘I was just borrowing this off a mate, he didn't tell me it was stolen.’ Sometimes those people have been lying to us but our job is just getting the bike back quickly and safely.”

Dunn said public and police attitudes have failed to keep up with the reality that bike theft in the capital is increasingly causing real economic and societal damage. Cycling in the UK was traditionally seen as a leisure activity, he said, meaning that while cycle theft could be “a bit of a pain in the ass“ it was also perceived as a low-priority crime: “You've had your weekend toy stolen. Boo-hoo.”

Now thieves are increasingly targeting larger e-bikes used by families or tradespeople as car replacements by people trying to beat London’s traffic: “These are typically four, five, six thousand pound electric cargo bikes that are used day in day out.”

This means thieves are developing new tactics: “Two young lads turn up early in the morning on mopeds. They'll cut it free and they’ll lift the bike up by one wheel. One lad will ride the moped, the other will sit on the back of the moped and they tow the cargo bike away very quickly.”

Dunn said they have seen some bikes get shipped abroad but this new breed of e-bikes are much bigger and harder to transport: “I suspect that these actually might be staying domestically and getting resprayed and sold on Facebook Marketplace. You can still get two or three grand for them secondhand.”

After three hours of staking out the same block of flats, I gave up and headed home. There were no more leads, the police would not attend the scene, and I began to accept I was never seeing the family bike again. I’d knocked on several doors to ask if anyone had seen a person dragging a heavy bicycle into the building. I’d developed the feeling that some residents were keeping an eye on me, watching my every move around the building, and waiting for me to go. And to be fair, I’d be the same if a stranger was hanging around in a stairwell on a Friday night.

Then, ten minutes after I left the building, the bike was on the move. First the AirTag pinged at another block of flats the other side of a park. I ran over there but was unable to find anything. Then it pinged one final time, a further 500 metres away. The signal was weak but it was all I had to go on. I sprinted down the road, into a dark car park, and saw my family bicycle leaning against a wall. Next to it was a man, dressed all in black with his face covered in a ski mask, standing by a black hatchback car with the boot open. He appeared to be getting ready to load the bicycle into the boot.

High on adrenaline and shaken by the situation, I blurted out the words: “I’m terribly sorry, but that’s my bicycle.”

The man looked understandably shocked. He replied: “Oh yeah? Well… I’m just going to my mate’s house upstairs.”

“I’ll take this, then”, I said, putting my hand on the bike more boldly than I expected. Seconds later he jumped into the car’s driver seat and sped away, leaving me with my bike — albeit lacking a front wheel.

In a parallel universe, I’m still waiting for the Met Police’s follow-up call, and my bike is long gone in the back of that car, possibly to be sold on Facebook Marketplace or resprayed and sent abroad. I’ll never know if the man I saw in the car park was the same person who stole it from outside my house. Revisiting the site the next day, I found a woman in a nearby flat who said she had seen my bicycle being dragged to the car park just minutes before I arrived, at which point the thief had spotted the AirTag on the frame and removed it. The tracking device ended up at my local recycling centre, where it is still sending out occasional mournful signals like a distant spacecraft, cursed to live out its functional days in a pile of London’s detritus.

Dunn said he had sympathy with the Met Police’s response given their financial constraints: “You would honestly struggle to put bike theft quite high up the list when you look at what else happens in society — rapes, murders, assaults. It obviously and probably should be put lower down that pecking order.”

When BackPedal went to a recent meeting with the Met to discuss bike theft, the police revealed they had been allocated £10,000 to spend on a new anti-theft policy — about the same value as some of the individual bikes his company recovers. That said, there is some hope that a long term solution can be found with increased used of technology: “There was a massive increase in car theft in the 90s. And that eventually was fought back on and brought down by like immobilisers, alarms, people adopting steering locks.”

“I'm optimistic about us getting more bikes back. I'm not optimistic about fewer bikes being stolen in the short term.”

Simon Munk, head of campaigns at the London Cycling Campaign, said theft is one of the biggest issues holding back the growth of cycling in the capital: “Around a quarter of people who have their bike stolen in London don’t go on to buy another bike. It massively impacts the kinds of people who cycle.”

He said bike theft is “clearly not a priority” for the “overstretched” Met but officers would love to catch bike thieves, not least because they’re often involved in other crimes: “It’s not that they don’t care. Their take is just that they don’t have any resources for this at the moment.”

Instead, he said some of the best work has been done by the separate City of London police, the small force that polices the Square Mile. They’ve had a high-profile success with a GPS-enabled bait bike, waiting for it to be stolen then smashing an organised crime gang by locating its storage unit: “For the Met, the massive win would be to go after the gangs.”

Munk said are “marked differences” in the way Germany, France, and the Netherlands approach bike theft, whether it involves mandatory bicycle registration, improved on-street bike storage, and broader cultural change: “The Dutch have low levels of bike theft because they tend to ride very cheap simple bikes and leave them unlocked. Because there’s so many and everyone owns a bike you can’t resell it for high levels of money. In the UK cycling skews towards middle-aged men with high income and you’re riding for miles in hostile areas of London in terms of route safety. They often own flasher road bikes, so that skews very different from the cycling culture in other European cities.”

Taupitz, the boss of insurance company Laka, said he still has hopes that more aggressive policing and improved technology could quickly undermine the big business of bike theft in London. It just needs a mix of new technology, political will, and funding for the police: “Nothing would be worse than people stopping cycling. There are solutions out there.”

Any feedback on this edition of London Centric? Have a story to share? Get in touch by emailing jim@londoncentric.media or contact me on WhatsApp.

If you’re not already a paying subscriber to London Centric, please consider taking advantage of our launch offer and signing up now.

Cracking piece. There is a potential solution. Register every bike frame with BikeRegister.co.uk. Then make it mandatory for every online sales platform (Gumtree, Facebook Marketplace, ebay) to list the registration number, with autolookup for stolen models. Microdots in the frame make it impossible to renumber a frame.

I've spoken to BikeRegister and a number of other orgs about this - all doable. It's something that's been spoken about for yonks. The only obstacle is political will. The Dept of Transport were looking into it...five years ago. Still nothing.

Fascinating article. When did London turn into New York or San Francisco?

Who are the thieves?

Why are police disinterested?